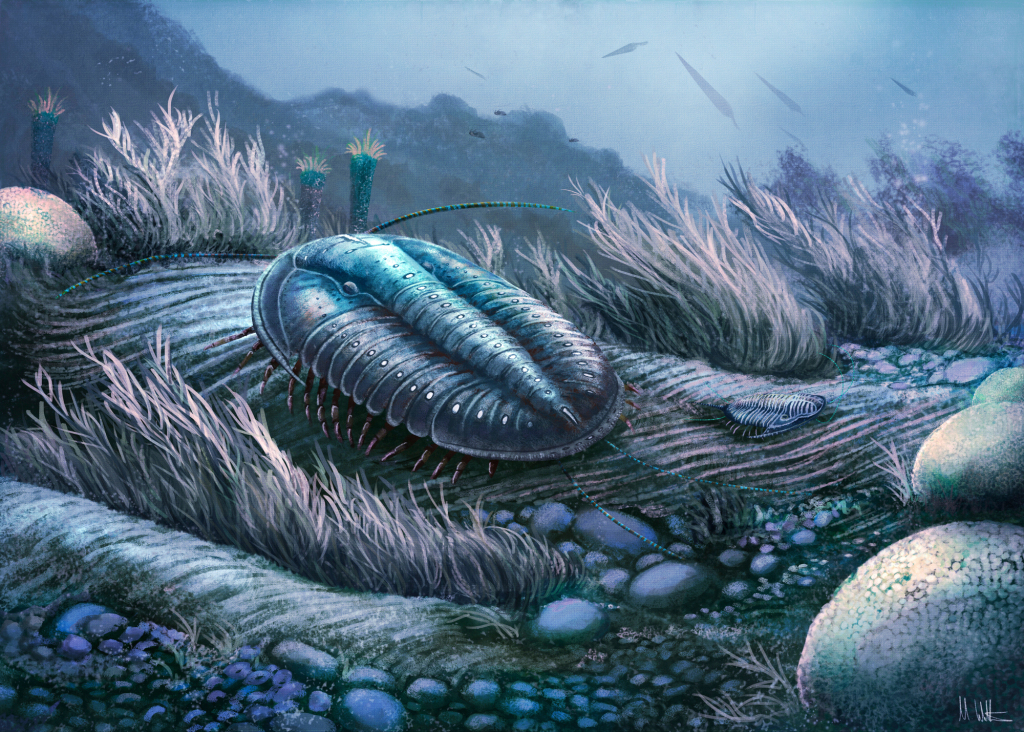

I’m a palaeontologist by training, obtaining my PhD back in 2008 after several years of studying pterosaurs (flying reptiles that lived alongside dinosaurs). But I’ve also always been a keen amateur artist and started drawing dinosaurs and other extinct organisms at a very young age.

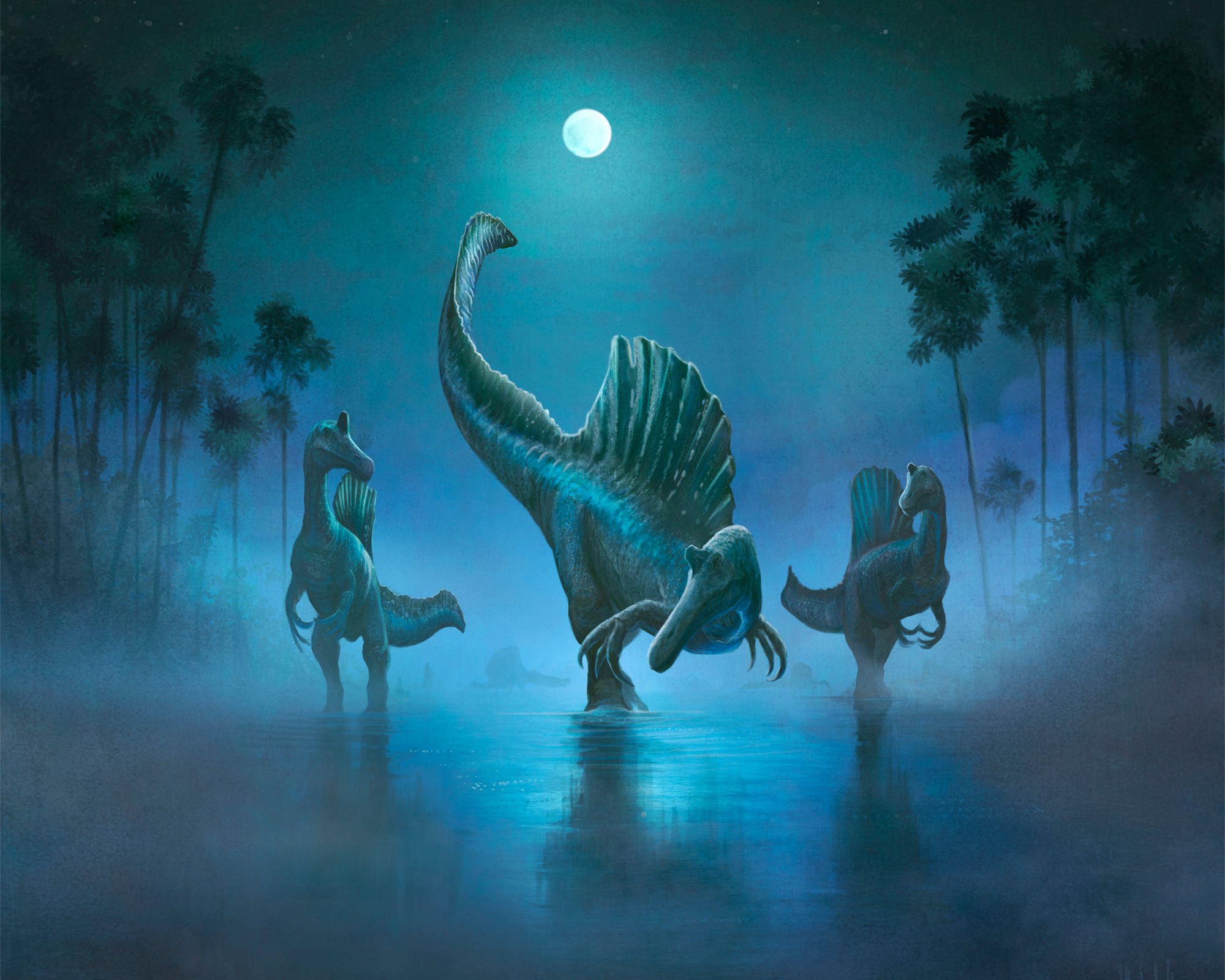

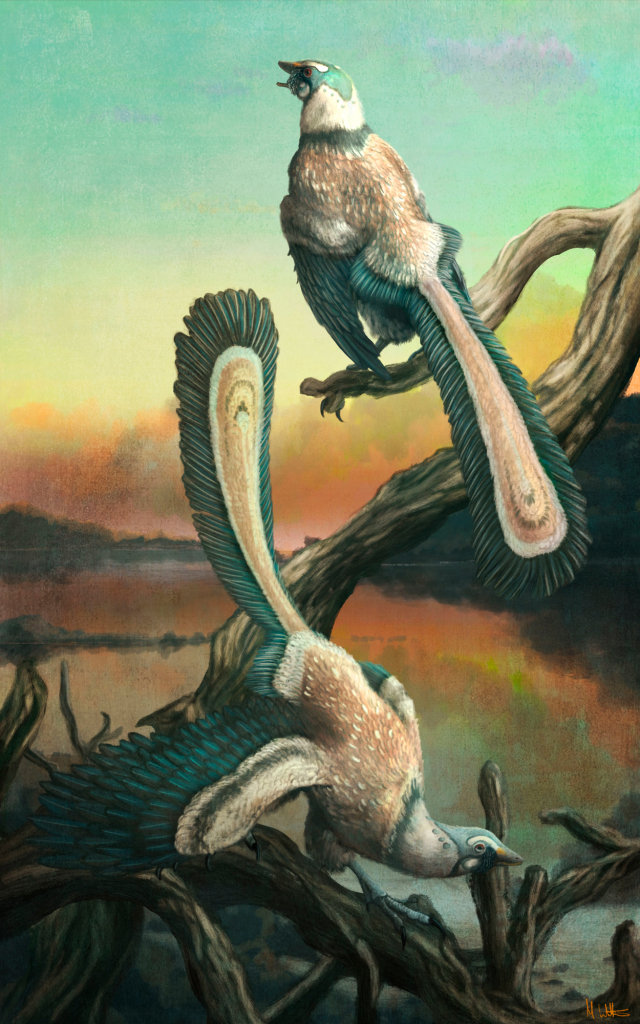

When I finished my studies, I began making a career as an author and illustrator, writing books on various palaeontological topics, including palaeoart, the art form devoted to reconstructing extinct species and landscapes using the best scientific data.

I now write and illustrate for a living, and also consult on palaeontological films and documentaries, providing concept art and designs as well as notes on their content and development.