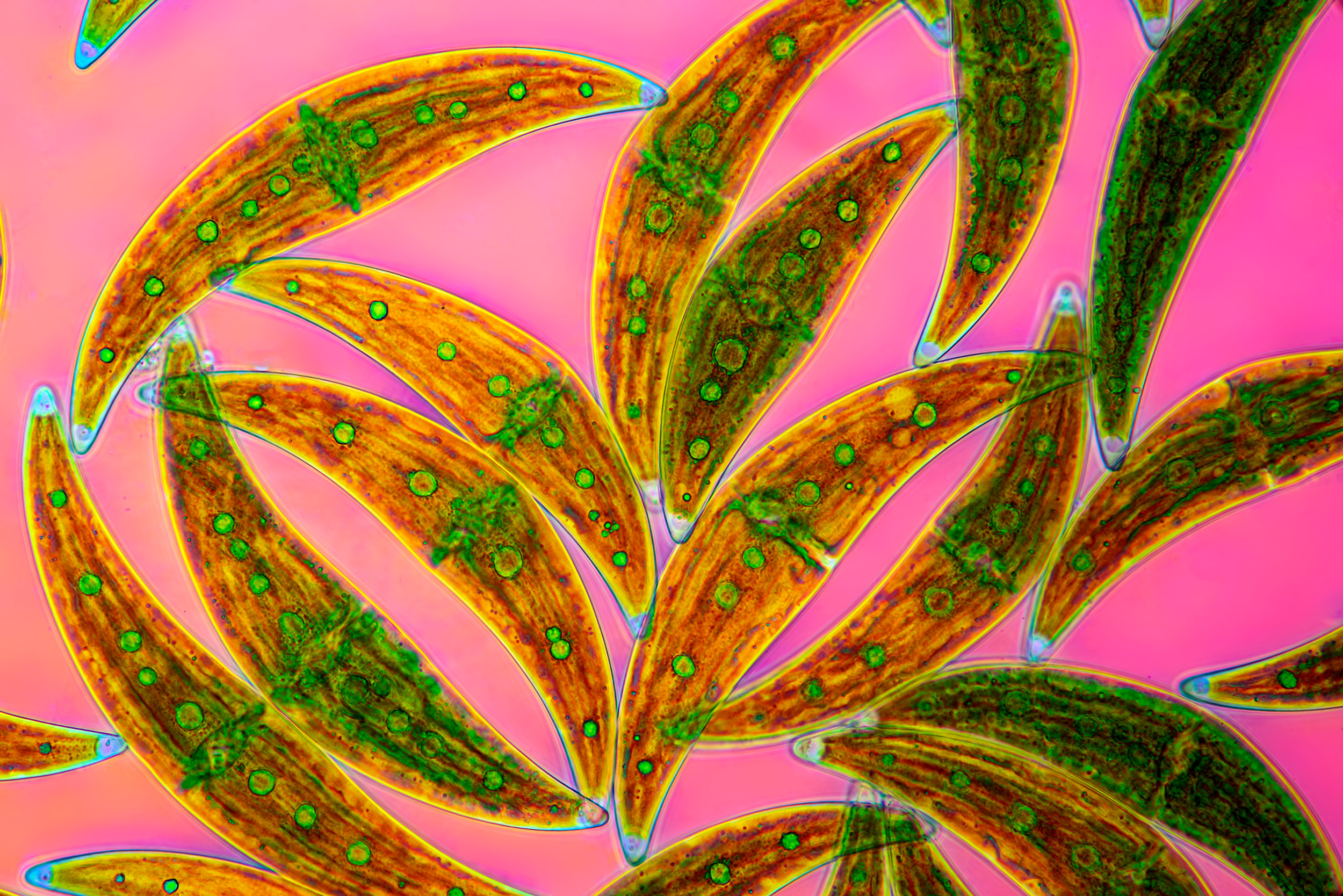

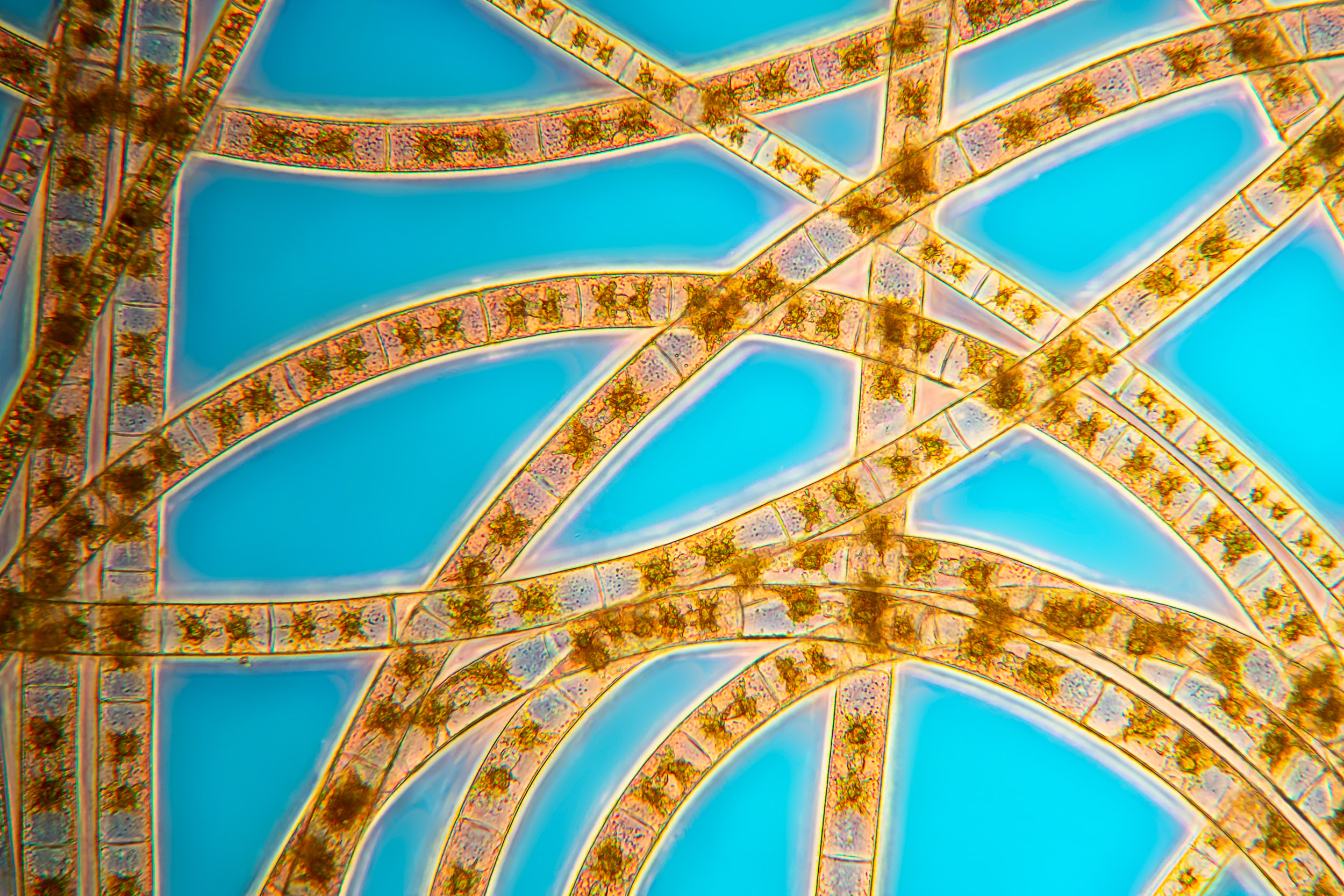

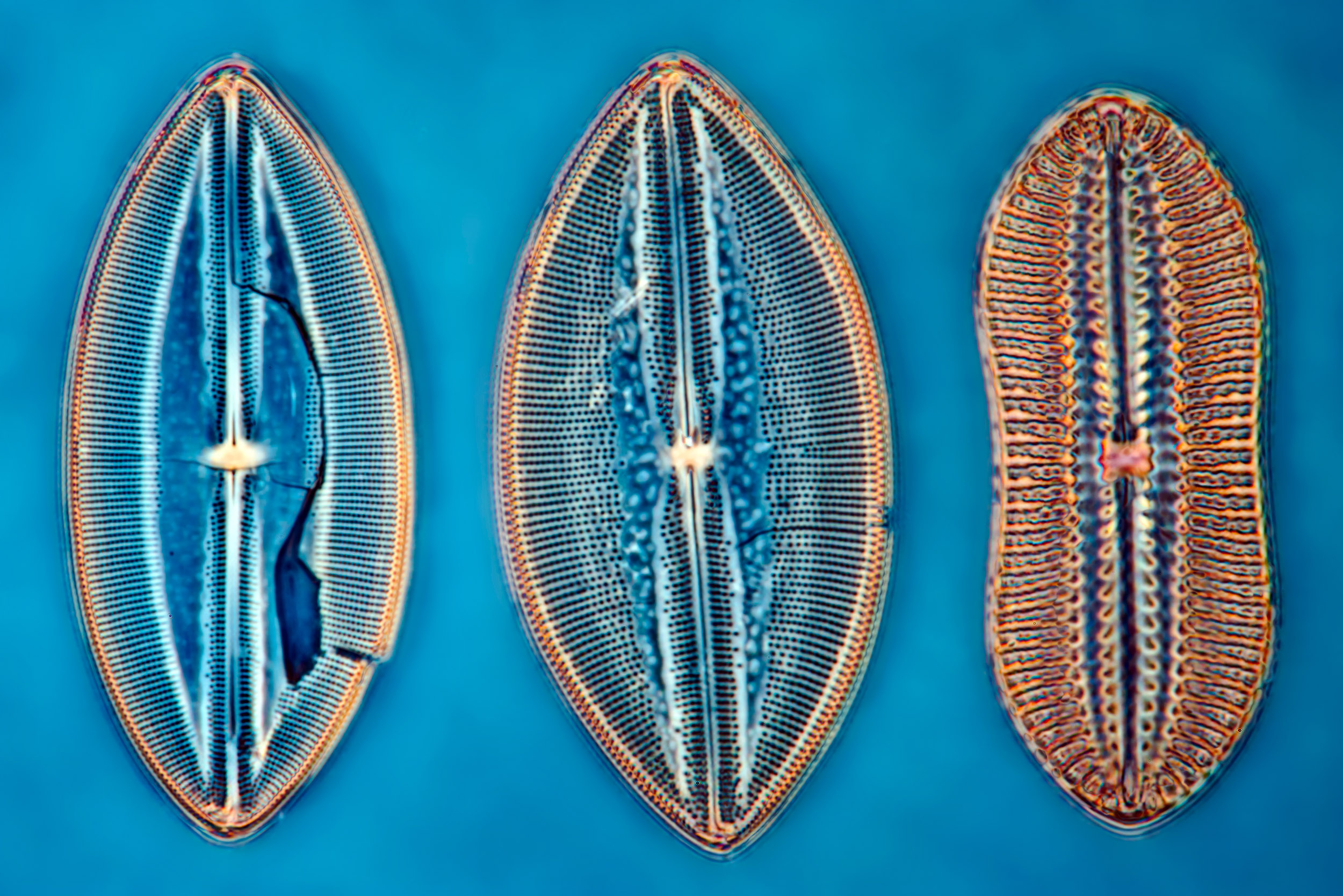

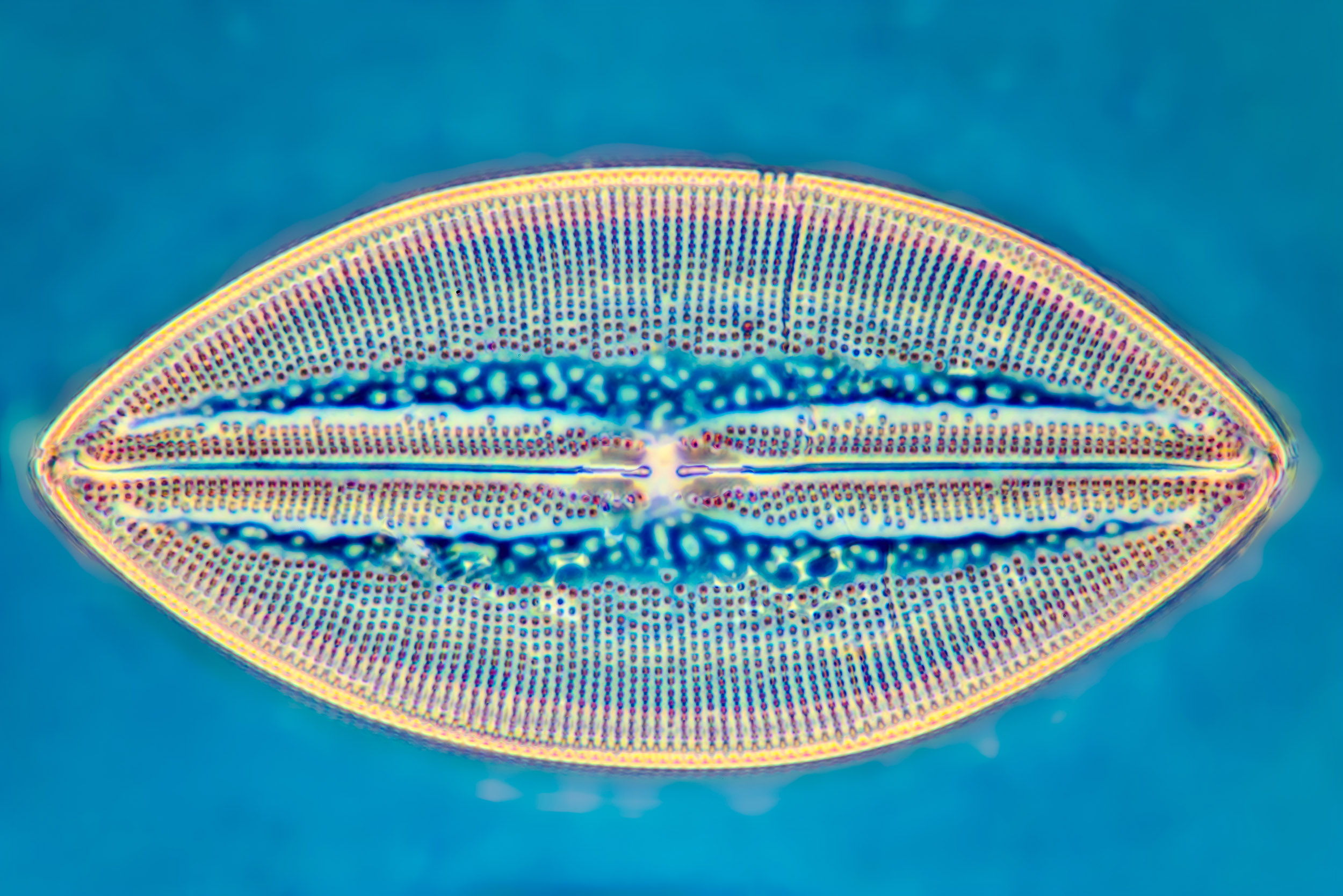

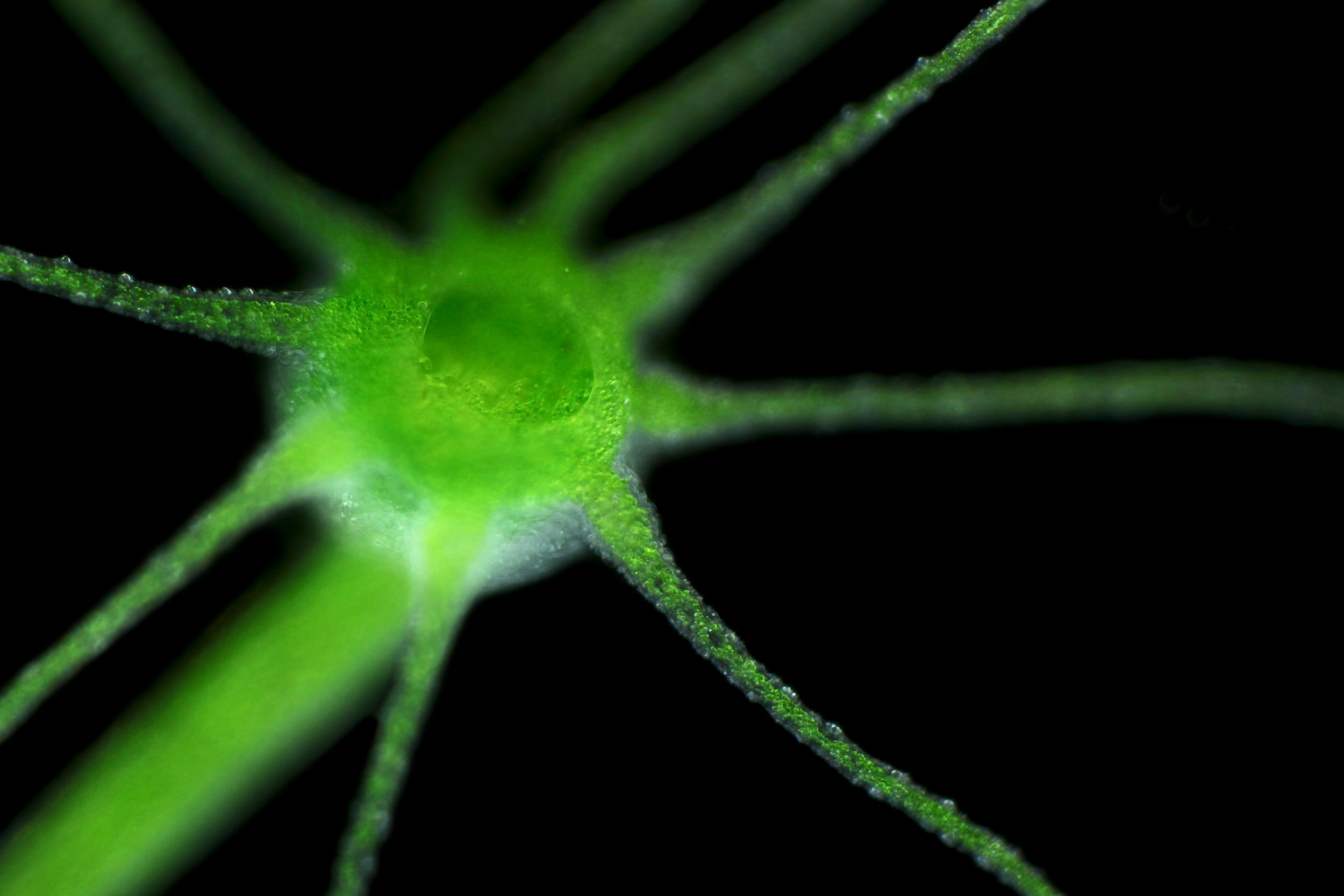

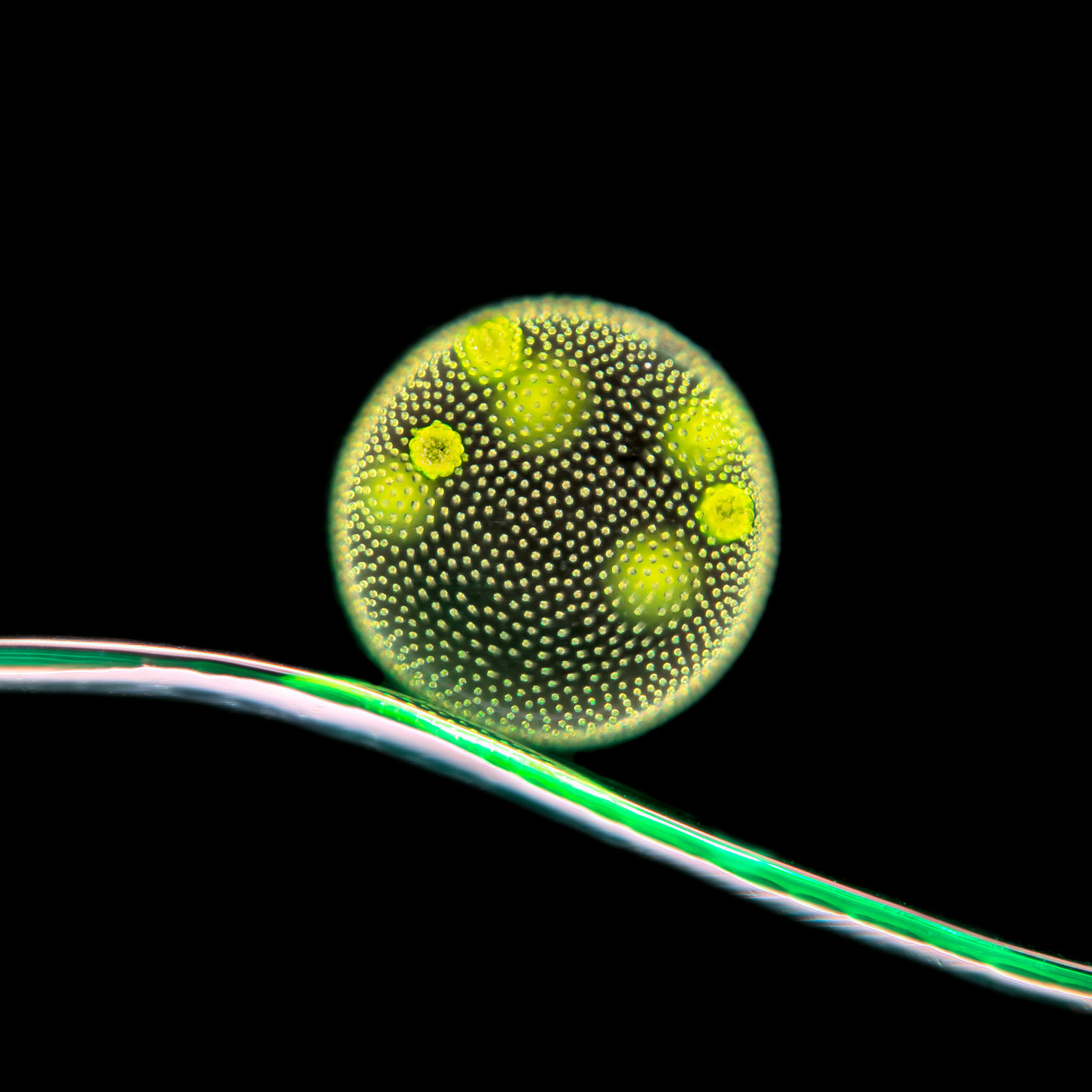

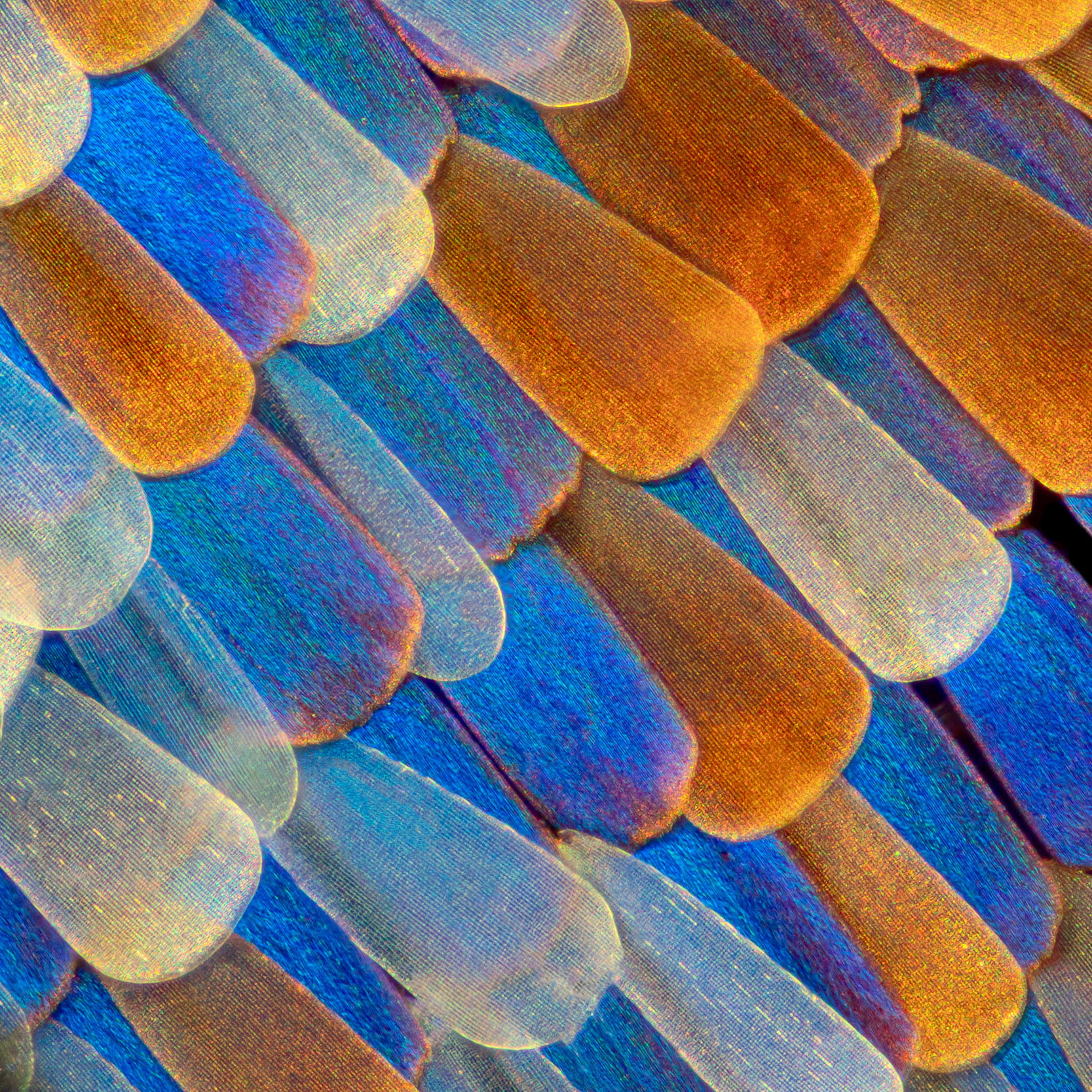

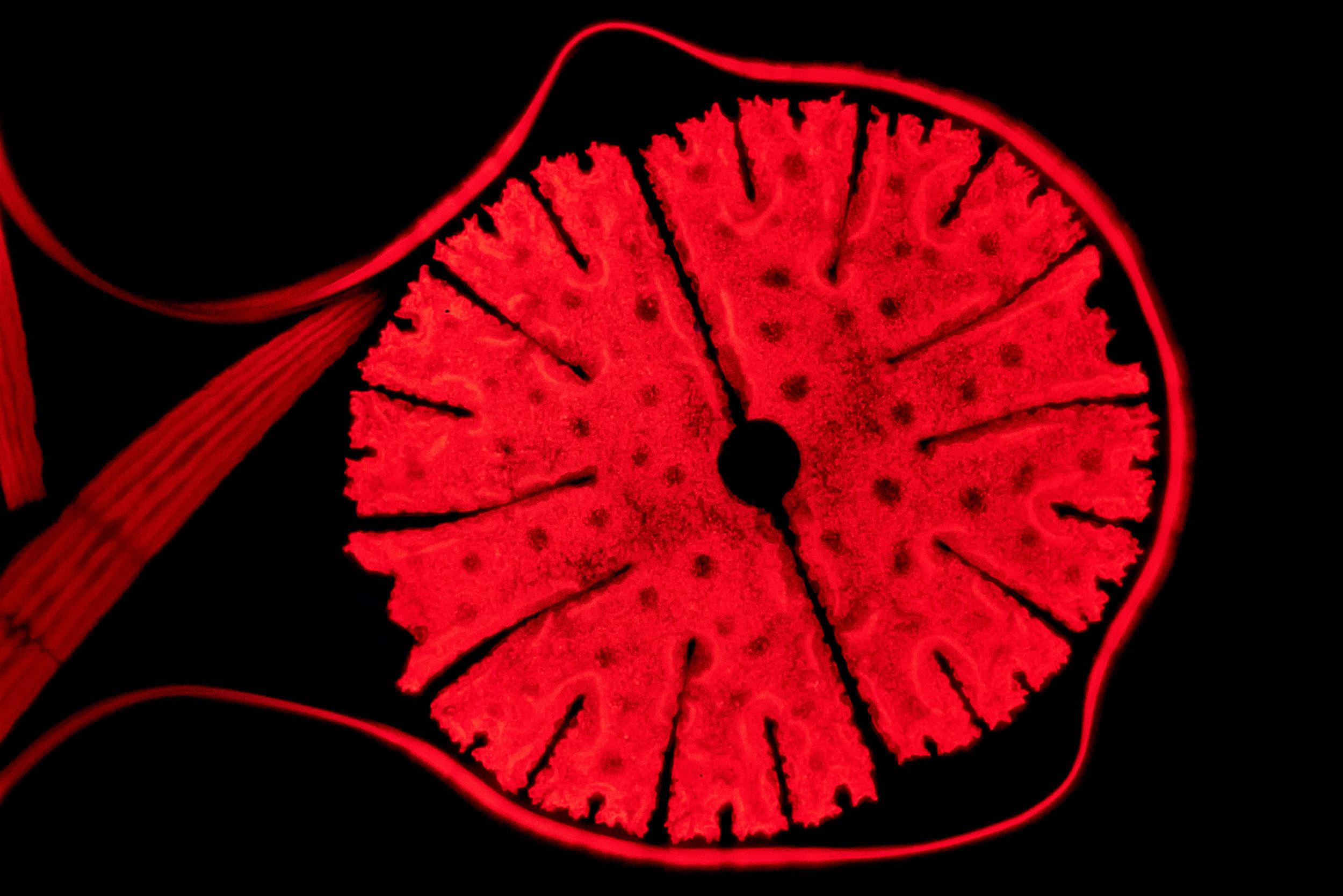

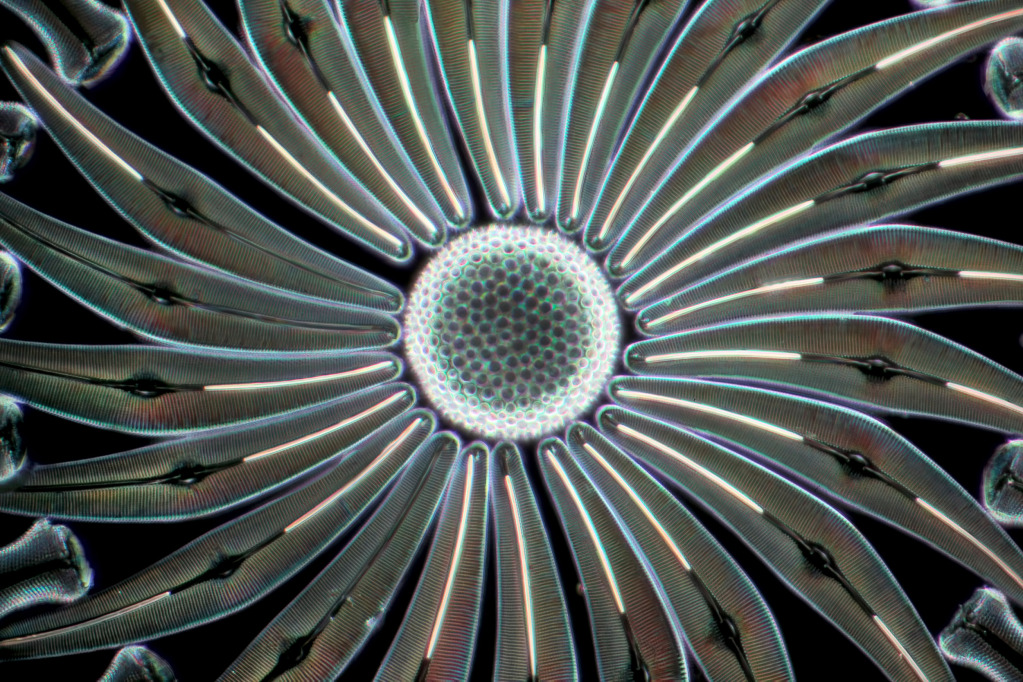

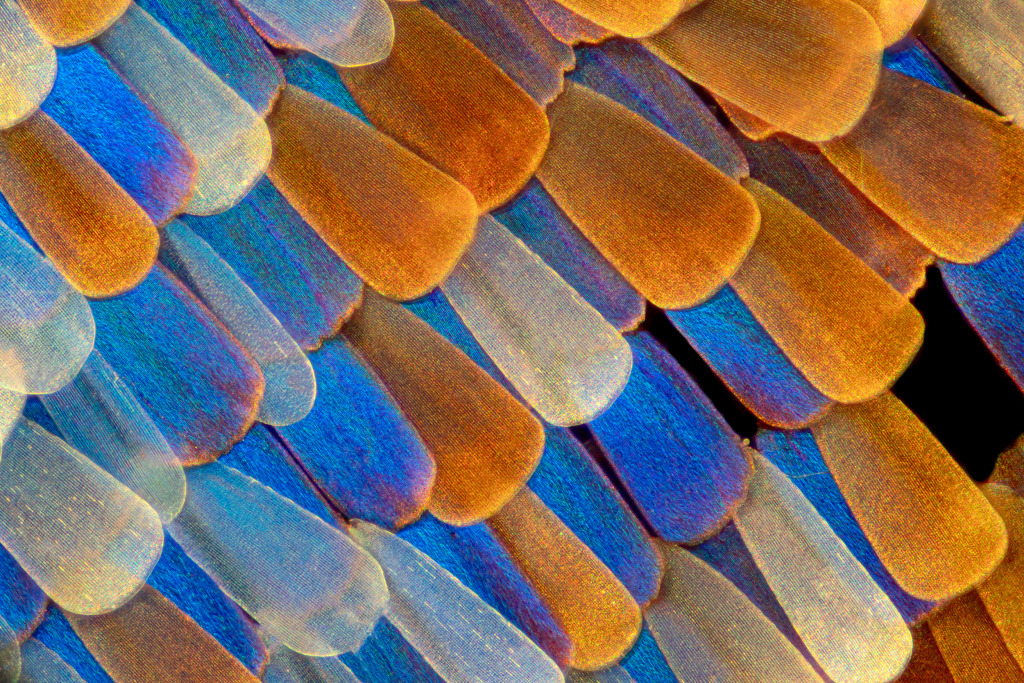

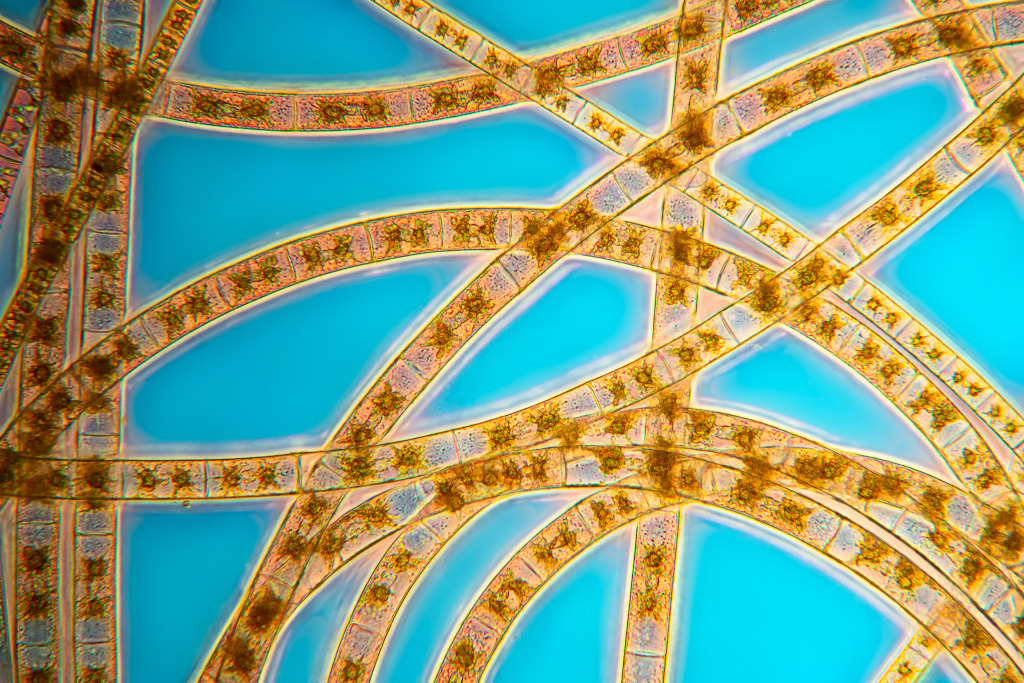

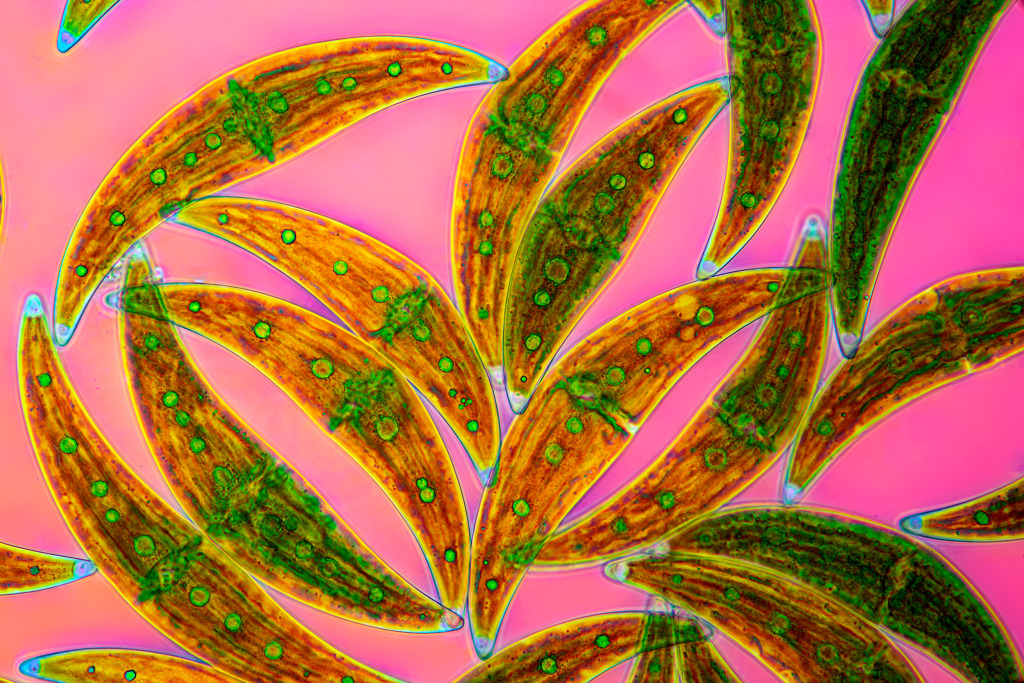

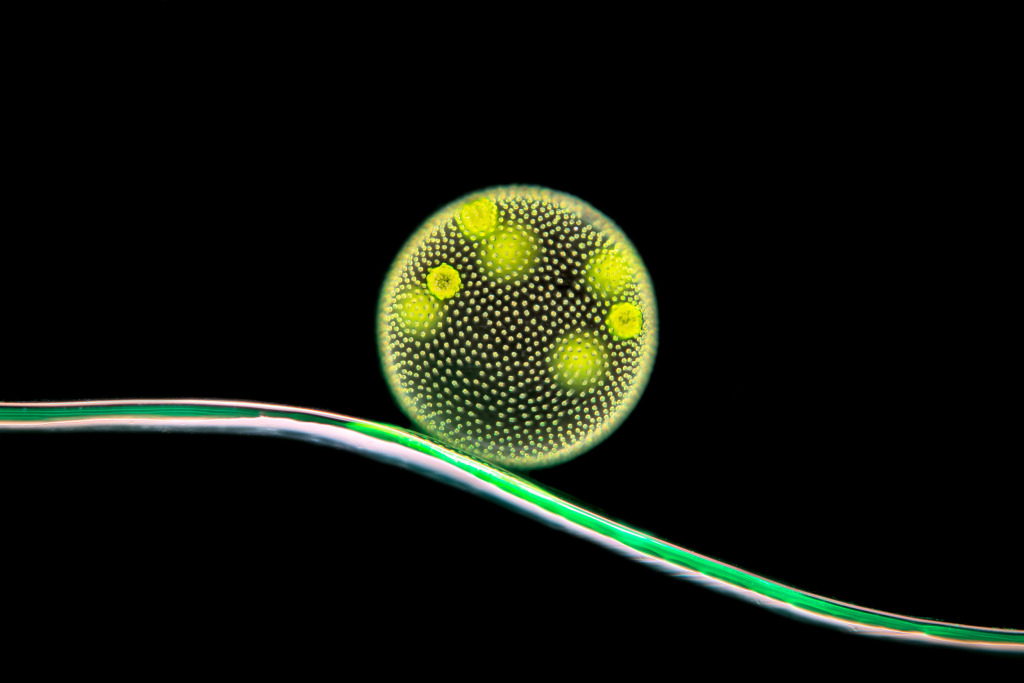

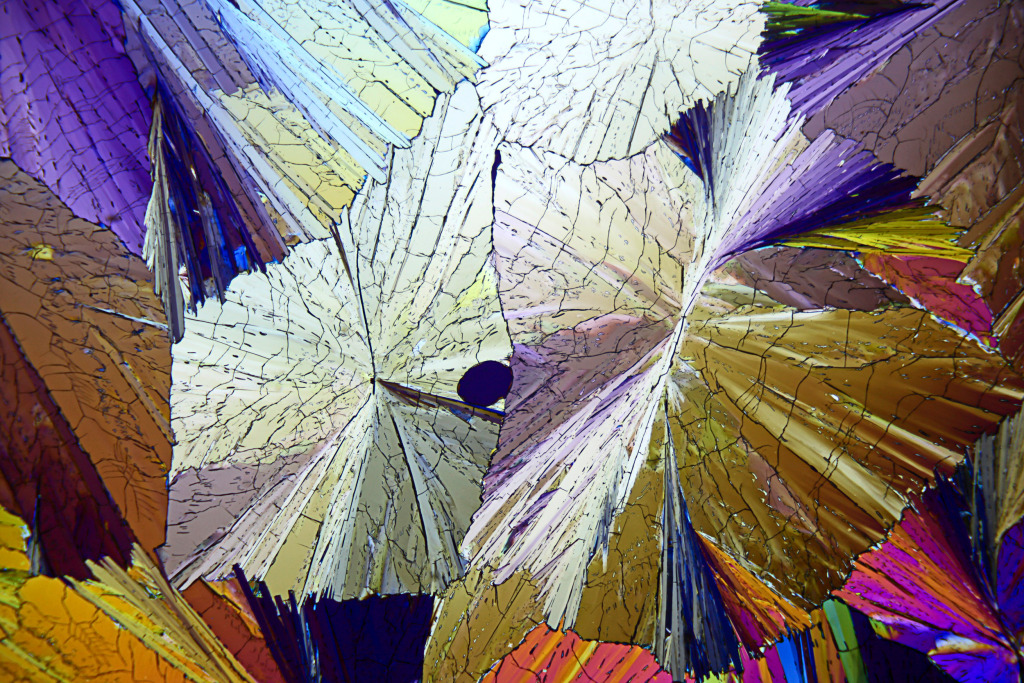

My interest in science developed early in my youth. I grew up in a small village surrounded by vibrant and beautiful nature. As a child, I was interested in observing insects and microorganisms in the streams and forests. Watching the development of butterflies or frogs was great. It was also around this time that my parents gave me my first small microscope, which although simple and made of plastic, increased my interest in the tiny world viewed through it.

It wasn’t until many years later, about 20 years ago, that a long-time photographer friend of mine rekindled my interest and I bought a professional microscope. Since then, micro and macro photography in all their facets have been a passion for me that I hope to experience for many years to come.