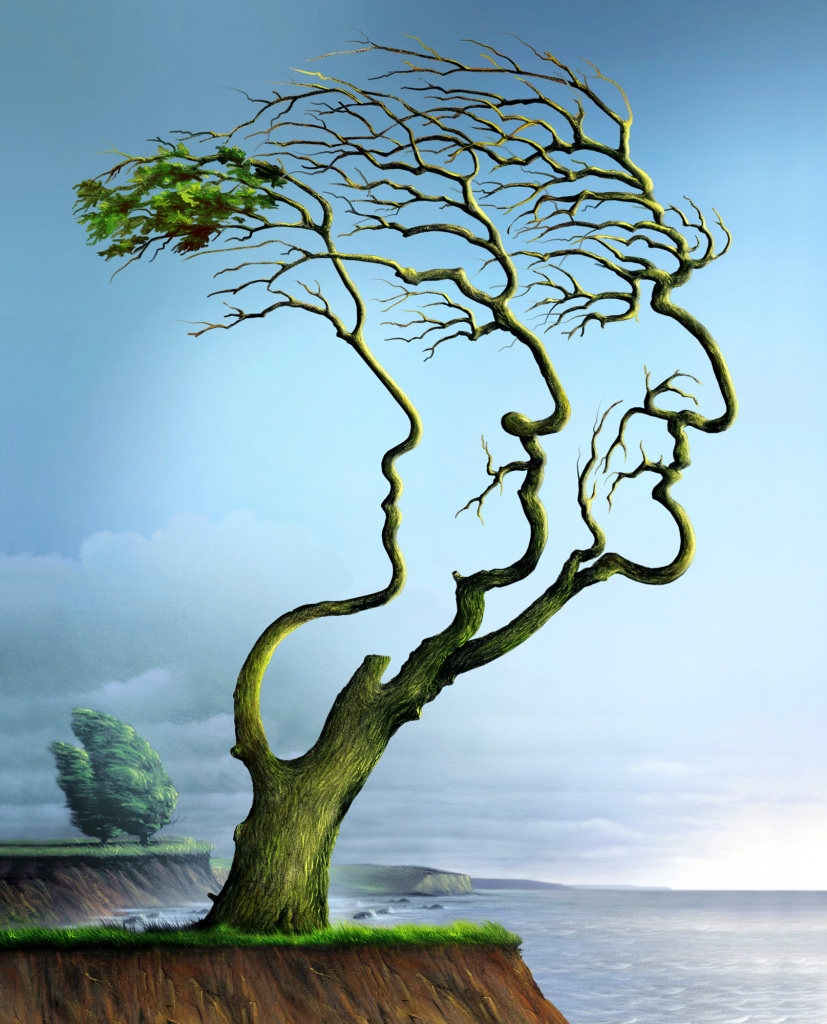

The prolific Polish political illustrator Wieslaw Smetek’s sharp wit and artistic imagination have graced the pages of many publications. Join us as we delve into Smetek’s creative process, exploring his inspirations, the role of satire in his work and the challenges of visual political commentary.

Wieslaw Smetek

Sharpening the Point

What initially sparked your interest in illustration as a career?

I never took illustration seriously, I was interested in posters. In post-war Poland, we had excellent poster artists. I wanted to make posters that were popular and talked about on the street. I knew illustrations only from the interiors of books, I appreciated them, but the poster was something more for me. I prefer larger formats and a clear message; covers of magazines have a similar function to those posters – clear message – short life.

Who are your artistic influences?

My development has been shaped by many artists.

The Polish poster artists Henryk Tomaszewski, Wojciech Fangor, and Waldemar Świerzy. The illustrator Saul Steinberg and also painters such as Picasso, Cézanne, and Vermeer.

Have you had any formal artistic education?

Yes, 5 years at the Art High School in Bydgoszcz and 5 years at the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk. It was 10 years of learning graphics at a fairly good level.

I also value these 10 years of learning art history very much. I consider this a very important aspect of our profession.

Can you describe how your style and approach to illustration has evolved over time?

The transition from manual work (struggling with matter) to digital (everything is possible) is an exceptionally significant moment in my professional experience.

Being born in 1955, I was not prepared for working on a computer. I resisted this leap for a long time. I was just scared as hell. In 1997 I had already printed a large number of covers for Stern and Der Spiegel, all made using one technique – dry pastel. The pastel technique is fast to produce but had to be delivered to the client by courier. However, it became obvious I would at least have to start scanning my work and sending it via the Internet.

My first testing of new technology, the first colour fax with a roll of photosensitive paper, was completely unsuccessful. I was forced to buy my first computer. A colleague advised me not to look at any textbooks, just work straight away. I struggled with the first illustration for a month, the client had fun watching, but suddenly I discovered that Adobe Photoshop was a tool invented for me. I was always exceptionally good at maths and geometry, and suddenly it turned out that Photoshop was wonderful fun with geometry. There was no problem painting with a mouse because it is the same as painting with a piece of pastel. I tried digital pencils but stuck with the mouse.

For me, the most important change resulting from this jump from analogue to digital is the increase in possibilities and the end of wasting paper. It didn’t affect my style, I just got a great tool in my hand. In the past, I sent 5-15 ideas to a client, but I was only able to implement some of them using the dry pastel technique. In the digital era, I can implement almost any idea myself.

Could you explain the typical workflow for starting a new illustration?

Stage one

Looking for ideas, the first one I write down with a pencil on paper in a quick form for me.

Stage two

Making several sketches for presentation as files. If the editors decide that an idea suits them, then the third stage begins – the implementation of the final product.

Final stage

Criticism from the client, making changes and looking for compromises. I believe that the willingness to compromise is quite important in the profession of an illustrator.

I believe illustration is a service. In my case, it is only made upon a customer’s request. My covers are usually created within 24 hours, sometimes 2-3 days, but sometimes also in 3 hours.

How do you stay informed about current events and political issues to ensure your work remains relevant?

I’ve been reading current news over breakfast since I was 14. It’s a pleasure, probably for many people.

Since the age of 14, I’ve been subscribing to two Polish weekly magazines – Polityka and Forum (Forum is a review of the world press). Of course, today I always have several sources of online information to choose from.

It seems obvious to me that people are interested in what is playing here and now.

Have you ever faced censorship challenges?

No never. Well, maybe I encountered a delicate form of censorship while working for Die Zeit newspaper. They were the first to introduce a voluntary quota for women. The Women’s Lobby at the time wanted to make sure Angela Merkel was portrayed in a “favorable light”. I found this rather amusing. Any quotas are a pathetic idea well used by the communists.

Have you ever experienced criticism of your work? How do you react to this?

In every job I am criticised for something, usually rightly so. Some people do it nicely and gently, others “show me where the pepper grows”. It’s simple, whoever pays has the right to criticise.

If you can’t stand criticism, practice pure art. Briefly, he accepts criticism in his profession without any problems, but criticism from his wife with difficulty.

Do you believe your work can be an effective tool for activism or social change?

Activism, yes, it can be. But social change? No, I have no illusions.

I don’t believe that aesthetics, illustrations or photos can change anything. Yes, sometimes an image can remain as an icon in society for a long time, but it does not change anything.

The art of propaganda wants to change society; nothing comes of it. It is the other way around, society processes propaganda in its own way.

After so many years creating satirical illustrations how would you say it has affected your view of humankind, if at all?

Practising the profession of an illustrator and satirist has caused me to notice childlike behaviour in adults more frequently.

I see adults as little children more often.