This beautiful Iranian proverb perfectly illustrates the world of Babak Tafreshi, whose work reveals the breathtaking beauty of the universe. Babak is a well-known Iranian-American photographer, science journalist and amateur astronomer.

Babak Tafreshi

Night hides a world, but reveals a universe.

When did you first become fascinated by the night sky? Was there a eureka moment?

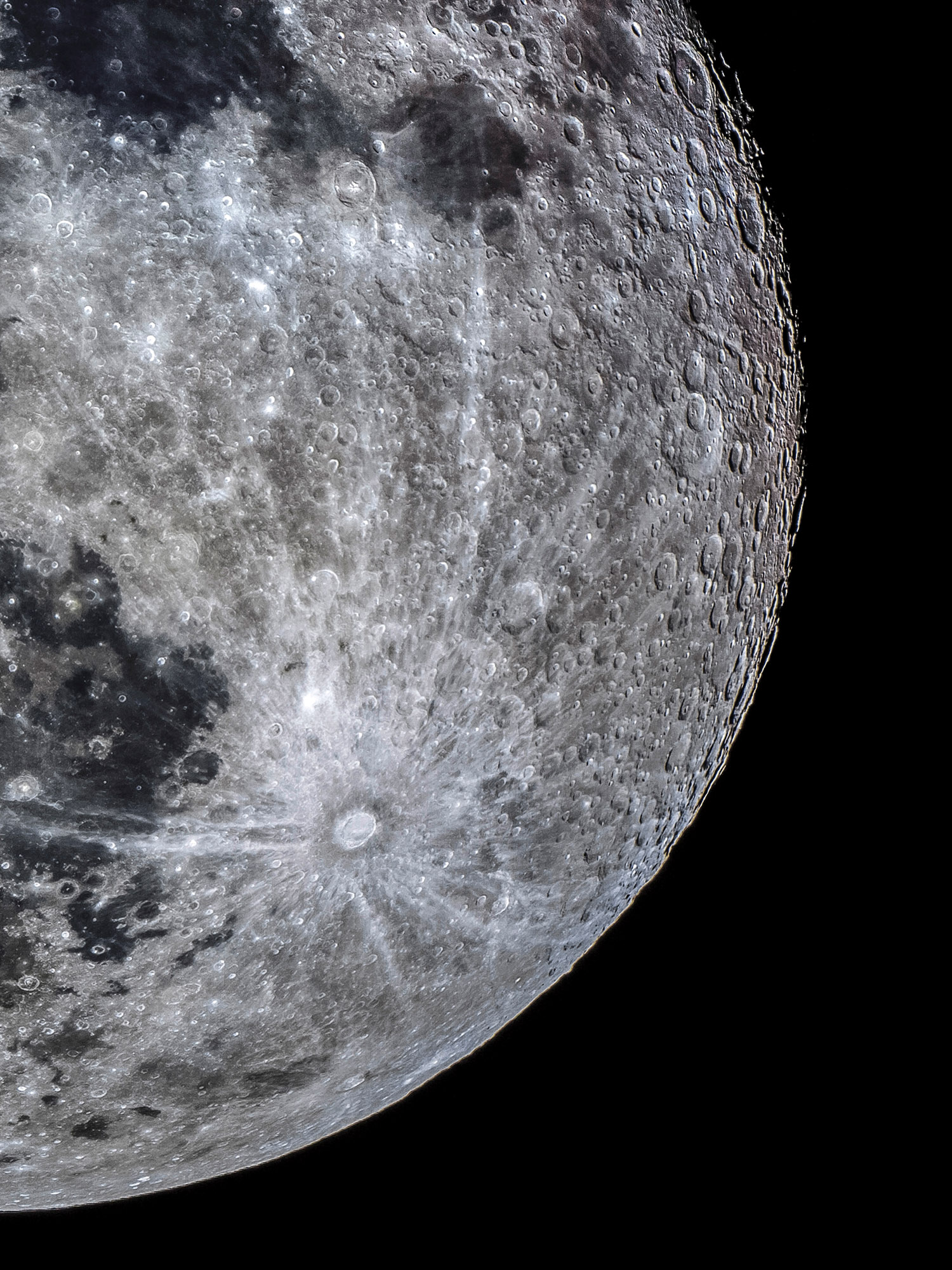

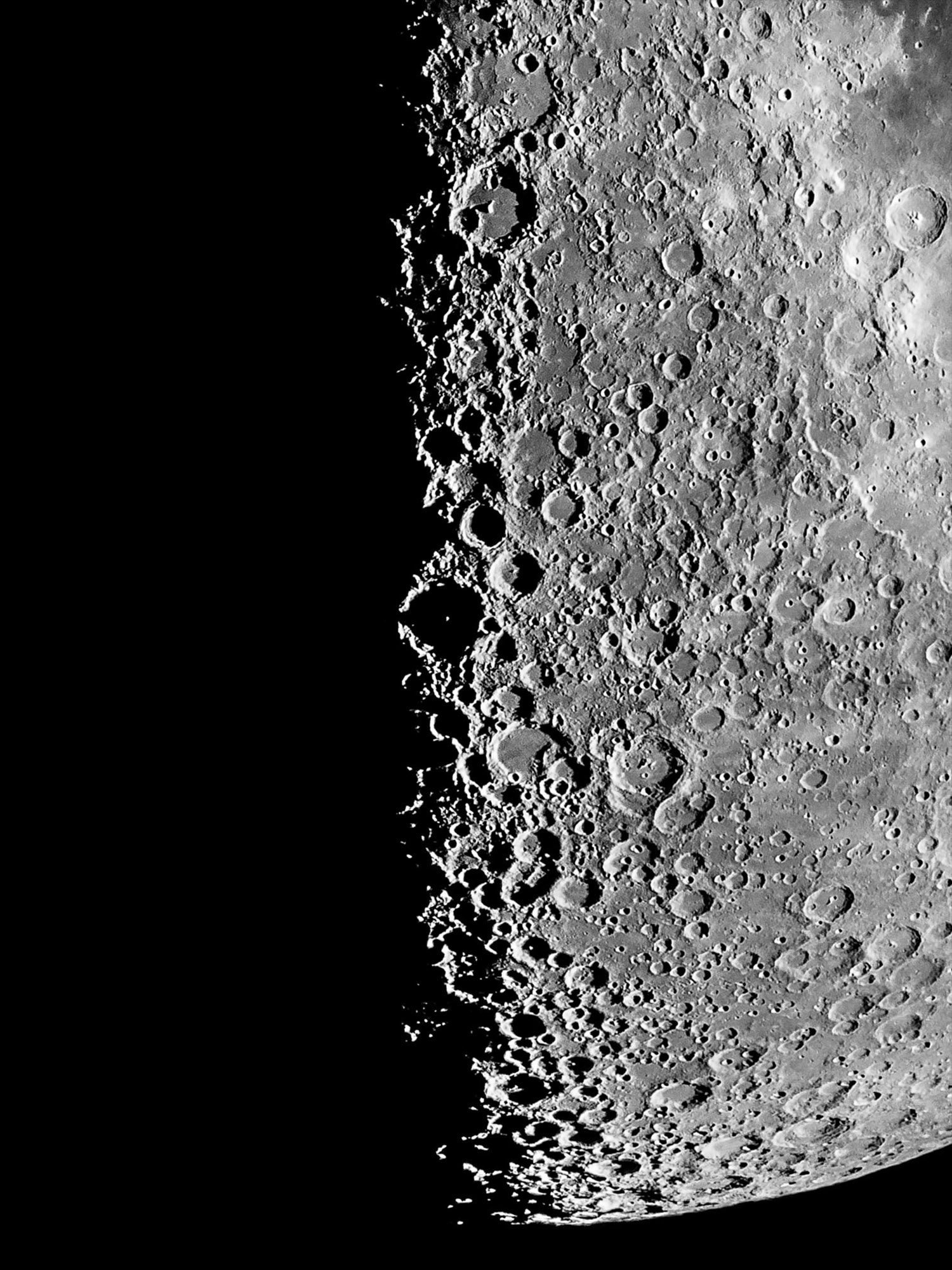

My passion for night sky exploration began the night I borrowed my neighbour’s small telescope and gazed at the Moon atop the roof of my family’s apartment in the middle of Tehran. I was 13 years old and still remember this moment second by second.

I couldn’t believe I could see so much detail of another celestial body through such a small telescope. I watched as the Moon glided across the field of view, exposing every crater and mountain. I felt like an astronaut watching from a spacecraft. I soon realized this simple look at the Moon had changed my life.

What led you from star gazing to astrophotography?

In my teenage years my high school friends and I searched for places with dark skies close to Tehran where we could use our telescopes and cameras. I began to document images through a telescope with a wide angle FOV and a simple SLR setup.

My first night sky photos were mainly long multi-hour star trails shot on low ISO slide films such as Fujichrome, Velvia 50 and Kodachrome 64. A few years later I began to explore other night sky events such as meteor showers, great comets, and a total eclipse.

In 1997 when the Comet Hale-Bopp became bright enough to be seen in Tehran, I travelled away from city lights to the Alborz Mountains and captured the comet on ISO 1600 film. This photo appeared on a couple of magazine covers and launched my photography career.

Did you ever consider becoming an astronomer?

As a teenager, I wanted to become an astronomer or planetary scientist. I began writing for a popular astronomy magazine while in high school. The senior editors gradually trained me to write about deep sky observation using small telescopes.

Although I studied physics at university, the magazine world introduced me to the power and importance of science communication. I recognized I could use my photography in the science visual stories I was sharing and my career took off. I must admit, however, that astronomy is my life!

Astrophotography is a very specialist area of photography. How did you train and were you influenced by anyone?

It began through trial and error in early 1990s in Iran, the country of my birth. It is a land of amazingly diverse landscapes and culture, and home to thousands of historical monuments. It has had a profound impact on my photography and made me a traveller from an early age.

In those years astrophotography articles in the Persian astronomy magazine (Nojum) and Sky & Telescope, took me and my team-mate Oshin Zakarian to the next step. We are still collaborating and often travel together.

One of my mentors since the early years of my career is David Malin, a British-Australian astronomer (now 80) and the world’s most accomplished astrophotographer. David had a profound influence on my photography. He developed several photo processing techniques and pioneered colour photography of the deep universe on film.

How do you decide where and what to photograph and how much preparation is required for an expedition?

Careful planning and a keen eye honed by years of experience go into determining what images I wish to capture. With the exception of 2020, I am generally on the road about half of the year.

I run six yearly workshops which keep me busy, as well as frequent National Geographic projects and speaking engagements that bring me to interesting places, and provide opportunities to photograph new scenery. Preparation for my imaging sessions must commence weeks in advance in order to be in the right place, ‘at the right time’.

Geographic location, altitude and temperature, Moonlight conditions, local topography, light pollution and many more factors are taken into consideration. And there is always the weather, ready to ruin an otherwise perfect session.

You’ve travelled the world to photograph the skies, including some very wild environments. What are the dangers you encounter and what are the benefits?

The dangers to night photography are mostly topographic obstacles. Our brain is not as sharp at night compared to day, and night vision is limited. One cannot always see the obstacles on the ground, or the edge of a cliff.

There can also be unpredictable issues with accessibility, wildlife, government restrictions, police wondering what I am doing out at 3 am with strange looking equipment. And human encounters, which are often more dangerous than animals, especially if you are on or near private property and the property owner is not aware of your photography plans.

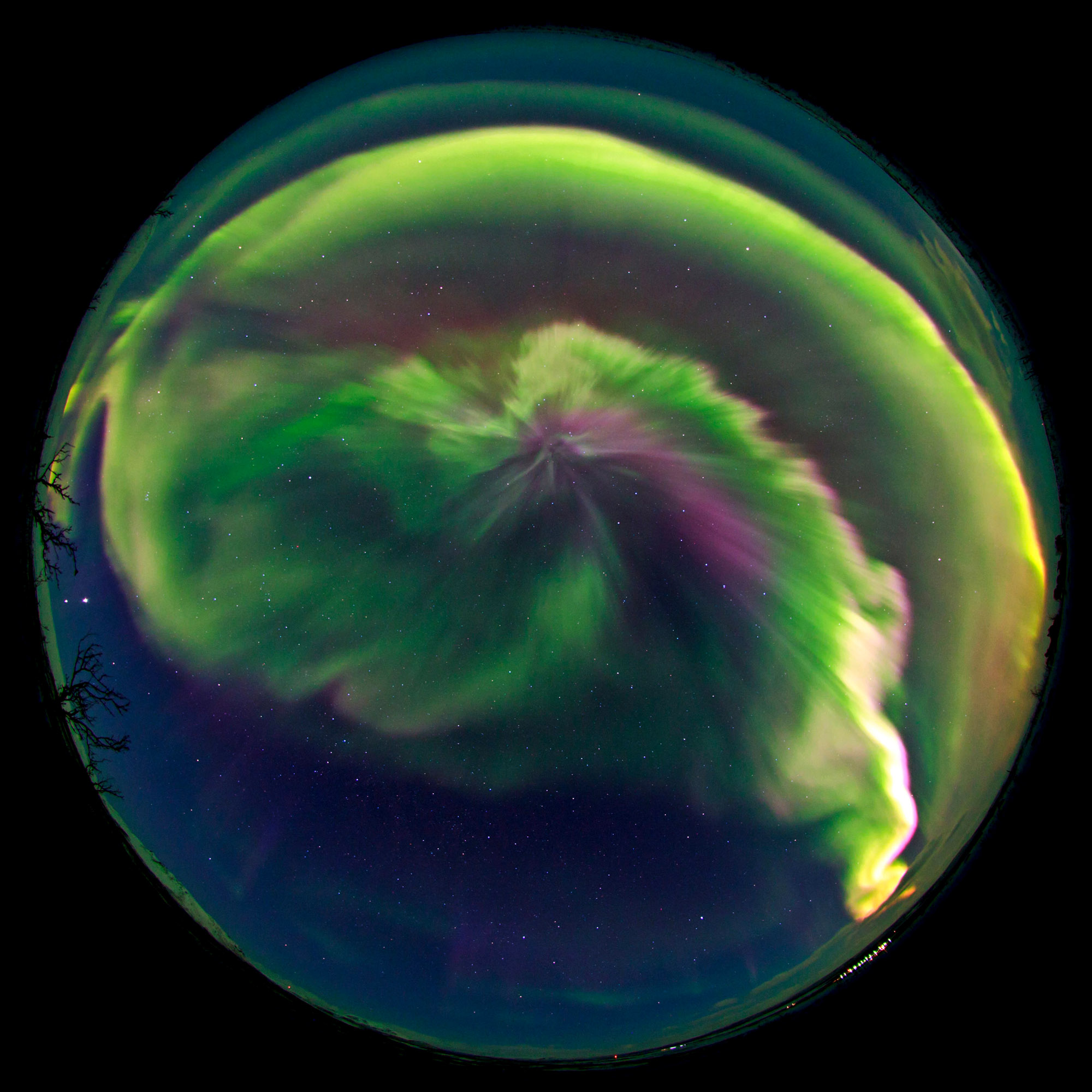

It is easy to get addicted to the night sky. The adventurous trips I make for my career are usually far away from the city, and far away from light pollution where the natural night environment is still preserved. These moments photographing the night sky bring me a sense of peace and unity with nature and the universe.

Do you work alone?

It depends on the goal of the imaging session or the work assignment. When celestial events are local, or when imaging at locations I have been to before, I generally work alone.

When I require assistance on a photography assignment, I often work with my long-time friend and photographer, Oshin Zakarian, whom I have known since childhood.

I also partner with my friend and night sky photographer and author Mike Shaw on a couple of workshops each year. We work together to scout locations, plan the itinerary, and choose program dates and goals for our workshops.

Any time I have the opportunity to work with one of my TWAN colleagues, I gladly do so.

Most of us never encounter the spectacular skies you see. What goes through your mind when you look up and gaze into the Milky Way teeming with billions of stars?

Taking photographs of the hidden Earth and shining sky offer experiences that go far beyond any technical or artistic enjoyment of photography.

I feel at one with nature when I am standing under an ocean of stars, listening to the sounds of nocturnal species, out in the fresh air.

Under a dark night sky, I feel peace and an amazing connection to both Earth and the universe beyond. I feel connected to the past and the future at the same time.

You founded The World At Night (TWAN), an international project showcasing stunningly beautiful images and videos by astrophotographers from around the world. Could you explain the goal behind this project?

‘One People, One Sky’. This is the universal message in our work. Regardless of religion, country or culture, there is one roof above all humankind.

TWAN was started in 2007 with a team of international night sky photographers who brought decades of experience and images to this project, which is aligned with nature conservation, art and science education, and humanity. Through photographs, videos, books, exhibits, and presentations, we aim to increase public awareness of the beauty and wonders of the night sky.

Our intention is to highlight the growing issue of light pollution and reinforce the values of preserving the remaining starry skies and natural night environment of the planet which is vital to many species. TWAN is a volunteer effort and relies on contributions by photographers, volunteer coordinators, and individual supporters.

What do you consider the biggest threats to the night sky and can they be overcome?

The night sky is not only a laboratory for astronomers but also part of our life. Almost everyone has a connection to the Moon and stars. It is instinct. Natural night is an essential element of our environment that is literally fading away in our modern society. Today most city skies are virtually empty of stars. Most of our youngest generation has never seen a dark night sky. About 80% of the population is now affected by light pollution.

The Milky Way is no longer visible, completely extinguished by city lights or excessive light sent to the horizon and carelessly pointed to the sky; outdoor lighting with strong blue-white 4000-kelvin LEDS worsens skyglow and adds to light pollution. Unfortunately, this type of lighting is increasingly popular, readily available, inexpensive and used to replace gentler, yellow light. As artificial light at night increases, the negative toll on natural night skies is becoming harder to ignore.

My colleagues at IDA (International Dark Sky Association) are working to provide advice, resources and lighting options that can be considered by local municipalities. Their recommendations help in the selection of lighting that is energy and cost-efficient, yet ensures safety and security, protects wildlife, and promotes the goal of dark night skies.

Does the accelerating activity in space by governments and private investments over the last few years concern you?

The main concern now is the number of mega-constellations being planned by companies and organisations. These are webs of networked satellites circling at a wide variety of altitudes in low-Earth orbit. Lower altitudes mean brighter satellites, although they remain visible for a shorter period of the night.

Unfortunately, these projects are not collaborators, but commercial competitors. The UN has not formulated a clear strategy on this. The astronomy community itself is too small to control it but the influence of its leaders in the political world can hopefully steer us to a common ground between the two sides.

How do you see future developments in technology affecting astrophotography?

Thanks to quickly developing digital camera technology embarking on night sky photography is now very easy, and is creating a fast-growing community of astrophotographers. Many newer smartphones are capable of recording acceptable low-noise images of stars and constellations in the night sky. Some already have the ability to record aurora and the Milky Way in real-time video when placed on a tripod for long exposure. With regard to telescopic or deep sky astrophotography, future technology will make ultra-sensitive cameras more affordable to amateur astronomers, enabling them to become prominent contributors to scientific discoveries in collaboration with professional astronomers. This is already happening.

On the other hand, we also see an outburst of newer night sky photographers making images that lack originality and story. The solution is to encourage the newcomers to learn more about our night sky. Although astrophotography apps make it very easy to plan the capture of the Milky Way or the Moon above a specific foreground, at a given time, it is still essential to learn the subject (as in any field of photography) in order to unfold all your creative options. A wildlife photographer, for instance, will achieve a more impactful portfolio if he or she learns more about the habitat and behaviour of animals.

Another side effect of the growing hobby of astrophotography is the increasing number of heavily altered and saturated images with unnatural colours or faked celestial elements. I see too many digital artists dominating this field of photography, producing a fantasy blend of various images taken at totally different times or locations. The originality, historic credibility, and value of the ‘moment’ are lost in such photo-montages. But the fast advancement of technology in both editing techniques and cameras is quickly diffusing the borders we make between real and fake images.

You describe your work as a bridge between art and science. You are a photographer, author, lecturer, and focal point for the community of astrophotographers. Do you have plans to develop in other directions?

For now, I will continue to document the last remaining starry skies on this planet. I will concentrate on raising public awareness of how important a dark night sky is, and why we should protect it from light pollution.

My mission is to share the importance and beauty of night skies. I have gradually become a ‘nocturnal species’ myself and consider it my second home. Light pollution is extinguishing the wonders and views of our night sky.

The true power of photography for change today is to document and share unique visual stories, especially environmental, social and cultural concerns and natural science stories. I hope my photographs can be a powerful educational tool.

Is there a corner of the cosmos that is particularly special to you?

Yes, Mars!

I have been obsessed with the Red Planet since the mid-90s when I started working as a young astronomer and space journalist. There is still so much to explore on Mars, and to understand if it was ever home to ancient life.