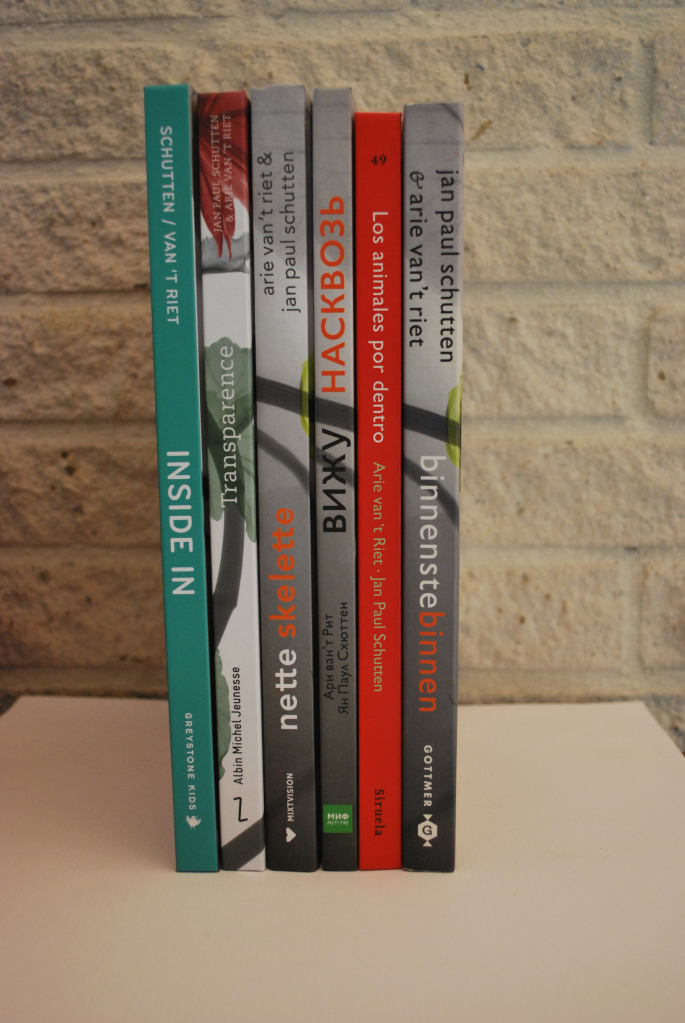

Welcome to the wonderful world of x-ray artist Arie van ‘t Riet.

Arie van 't Riet

Playing with energies

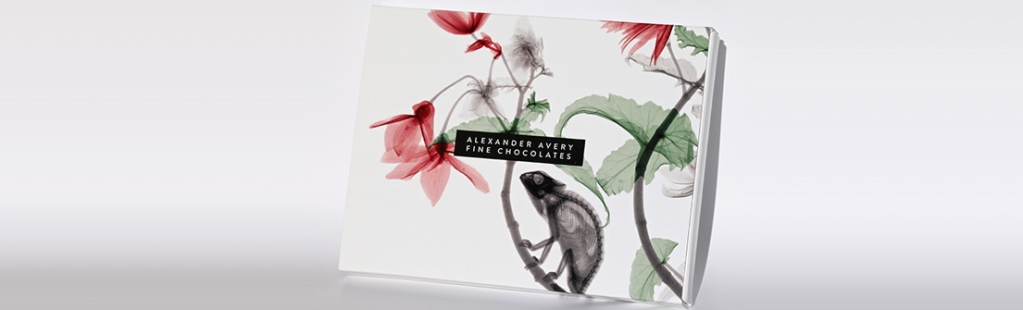

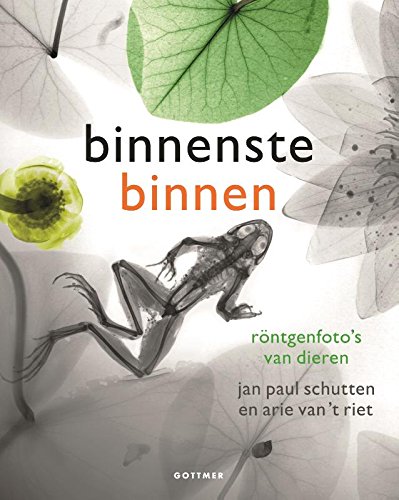

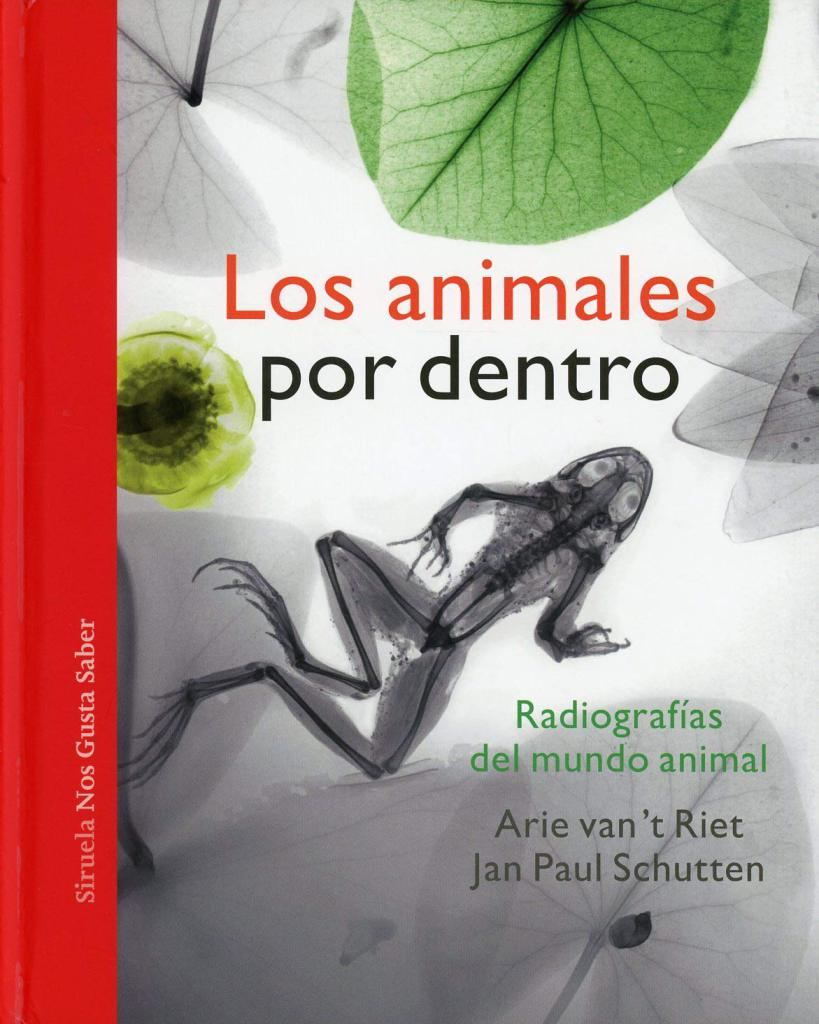

Arie runs his own studio in the Netherlands and owns the equipment used to create his stunning artworks. He describes his images as bioramas, based on the picture-viewing device known as a diorama which shows a 3-dimensional full size or miniature model of a scene. Arie’s amazing bioramas recreate natural environments, using plants and animals as his models, bringing them alive in a realistic landscape.

Arie believes it is not justifiable to expose living animals to the risks of x-rays just for artistic imaging. His specimens are not living and are collected from various sources. Arranging the specimens in the biorama in a naturalistic way is a complex art in itself.

The bioramas use 33 cm x 41 cm analogue x-ray film and are imaged as a whole in one session. They are not stacked or layered digitally. To create large bioramas a couple of negatives are positioned next to each other and after exposure are digitally stitched together.

Arie’s x-ray work is unique. It reveals an invisible world beyond human vision in combination with the natural world we are familiar with. We all know what a frog looks like but we don’t know what lies under its skin. His images allow us to look deeper into a landscape that is beautiful, delicate, playful and surprising.

You began your working life as a physicist: was there a particular moment or event that influenced this choice?

As a child living in ‘The Green Heart ‘of the Netherlands, I was fascinated by all the animals around me. Biology was my main interest, however an interest in physics was instilled in me by a very enthusiastic physics teacher.

Nuclear physics was the area that particularly fascinated me. This led to my graduation in radiation physics at the Delft University of Technology.

You worked for many years as a medical physicist. Did this involve working with images?

I mainly worked as a medical physicist at the department of radiation oncology. In this speciality, imaging is fundamental for tumour delineation and radiation treatment planning.

However, this kind of imaging doesn’t compare to what I’m creating nowadays.

In retrospect, was it a good technical and aesthetic training ground for the creative direction you finally made?

It was very helpful to develop the technical skills. The training in the x-ray department was of great value to me.

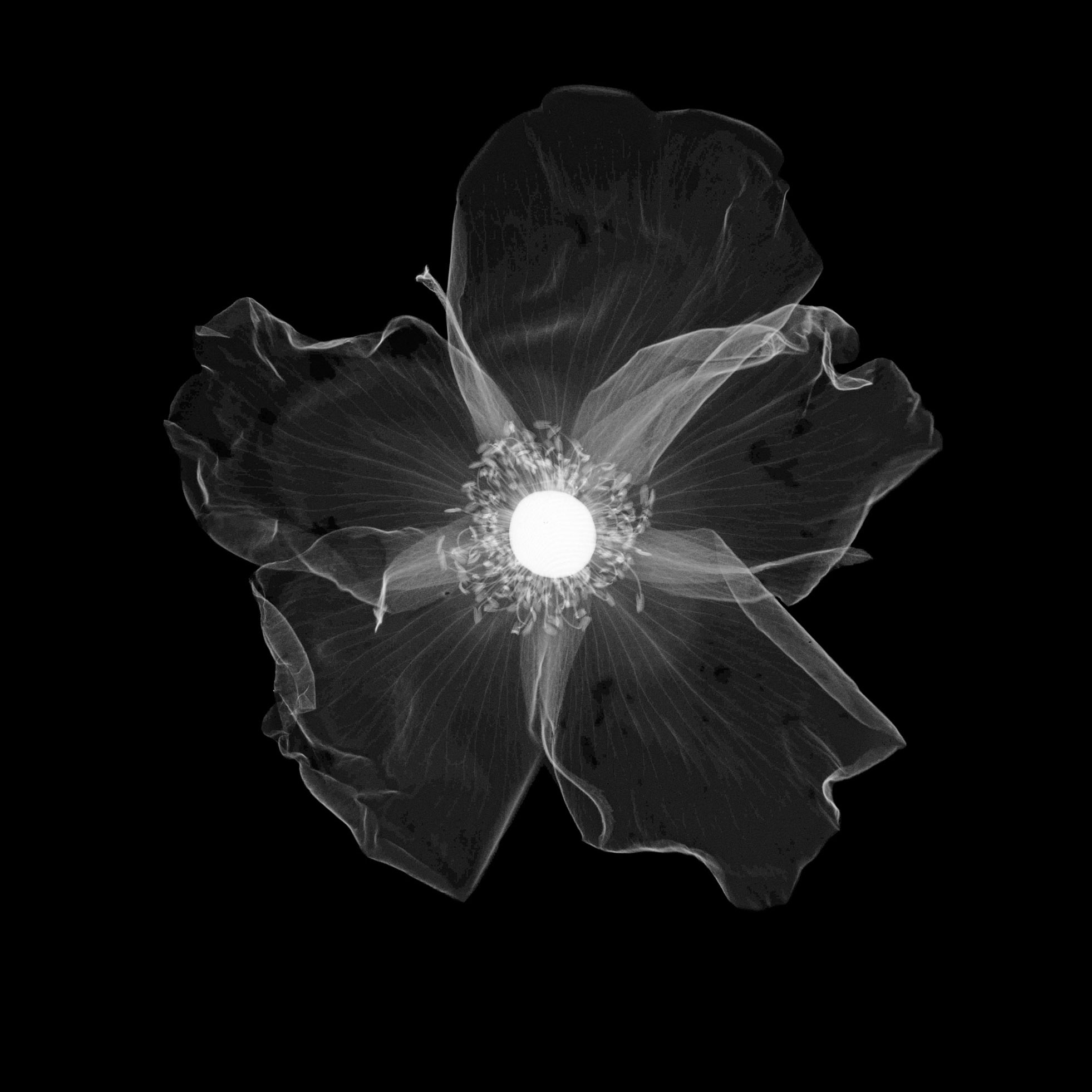

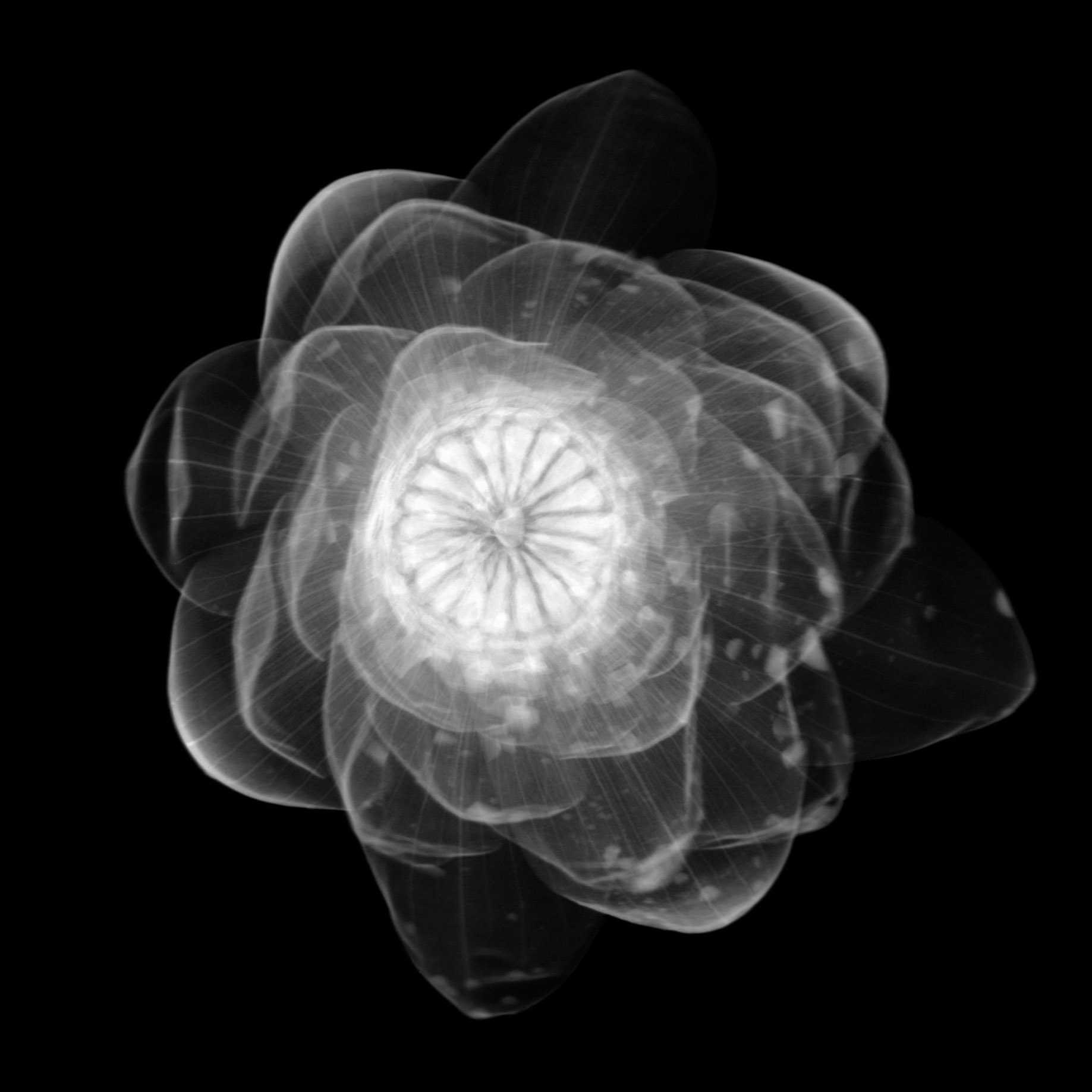

We practised with all kinds of materials such as aluminium, copper and lead plates. But we also used flowers, shells and other natural materials, which gave us a creative outlet.

Did the switch from scientist to artist come suddenly and as a surprise to you?

It just happened.

I started to digitise, edit, clean up and colour some of the flower x-rays that were shot during practical training. Acquaintances, friends and family saw them and encouraged me to continue.

There are only a handful of x-ray artists in the world. Your approach is unique, creating a holistic environment into which the viewer enters, wanders around and creates a story. You call these worlds bioramas. Can you explain where this delightful, playful, idea comes from?

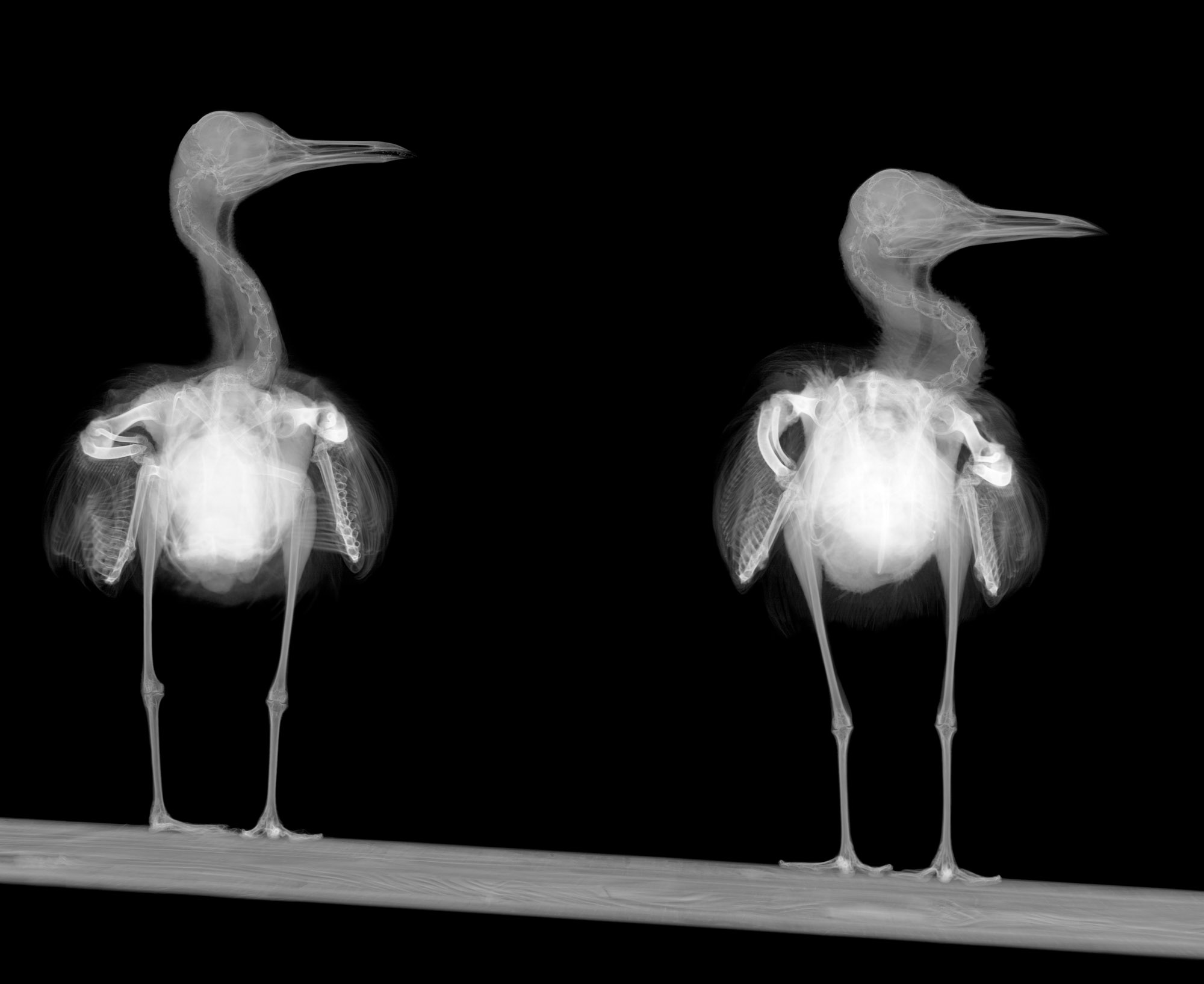

Animal specimens and plants coexist and that’s why I started adding animals. It was a pity that the exuberant colours of the animals couldn’t be captured, especially the birds. However, it gave me the opportunity to visualise their inner beauty, their complexity, functionality and similarity.

Diorama is a viewing cabinet, usually in miniature. The components in my viewing cabinets are exclusively biological specimens. That’s why I prefer to call them biorama’s and they are life-sized.

Creating a biorama is far more complex than simply x-raying an object. How do you create them and is the process challenging and time consuming?

The animal is the centrepiece. Once I have a specimen, I attempt to recreate its habitat by collecting the relevant natural parts such as leaves, flowers, plants and branches. Then these components are arranged in such a way that creates a natural scene (biorama). Conventional photographs are taken and I then try to imagine what the x-ray will look like.

An x-ray negative is slid under the biorama and the x-ray tube is placed above it. The x-ray is taken and assessed. Often the biorama is slightly adjusted and several x-rays are needed to achieve the desired result. It takes time and patience.

How do you collect your specimens?

The specimens I use for my artwork are often traffic victims. This varies between mammals, birds and amphibians. I buy fish at a market.

A friend of mine breeds reptiles, so he sometimes gives me one that has passed away. I buy preserved insects at specialist shops.

You add colour to your x-rays in a very deliberate way. How do you decide what structures to give colour and what to leave in the original black and white?

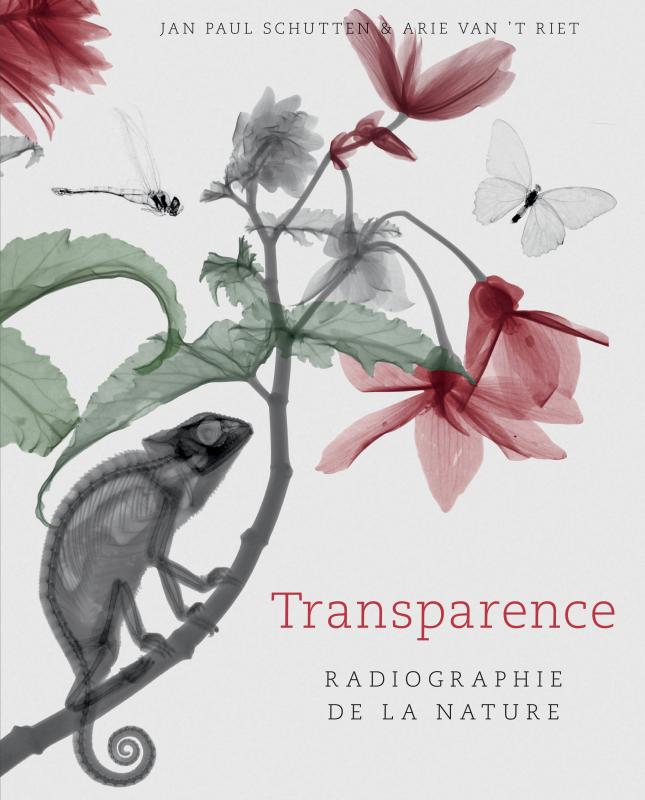

Colouring is restricted to plants and flowers. Animals are not coloured.

I think it’s almost impossible to digitally colour the animals naturally and preserve the transparency of x-rays.

The way in which I colour flowers depends on my inspiration. I don’t have any special rules.

How do you find inspiration for your ideas?

Once I have an animal specimen, I start buying some flowers and plants. I play around with it, until I like the composition (a biorama).

The absence of background is a characteristic of x-raying; nothing behind the negative is imaged. That’s why I often find inspiration in ink drawings or in graphic techniques (etchings, woodcuts and lithography).

Have new technical developments in the x-ray field contributed to the direction of your work?

The digitization of radiology in hospitals was very important.

It made it possible for me to pursue my passion.

Although the digital equipment was too expensive for me, as hospitals upgraded their equipment I was able to acquire their old machinery.

What is your favourite image in your collection and why?

I have two favourite images.

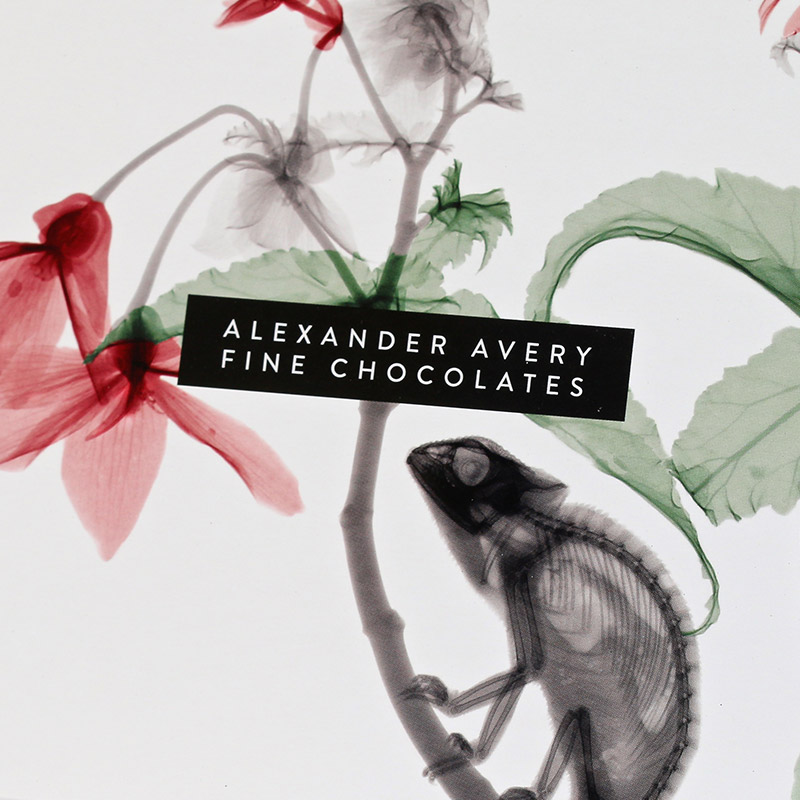

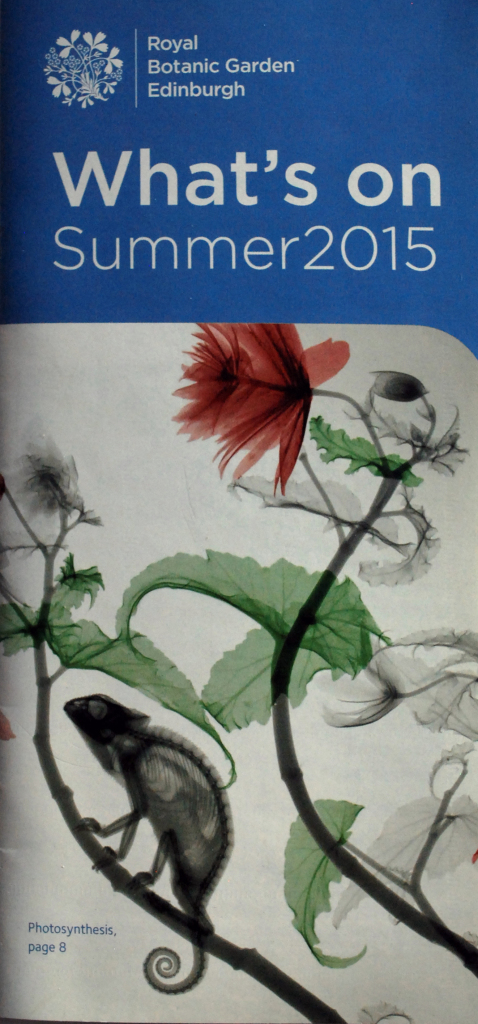

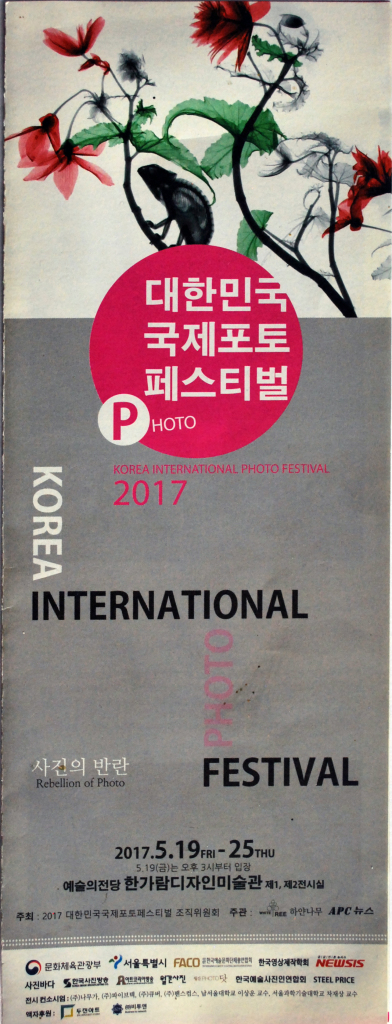

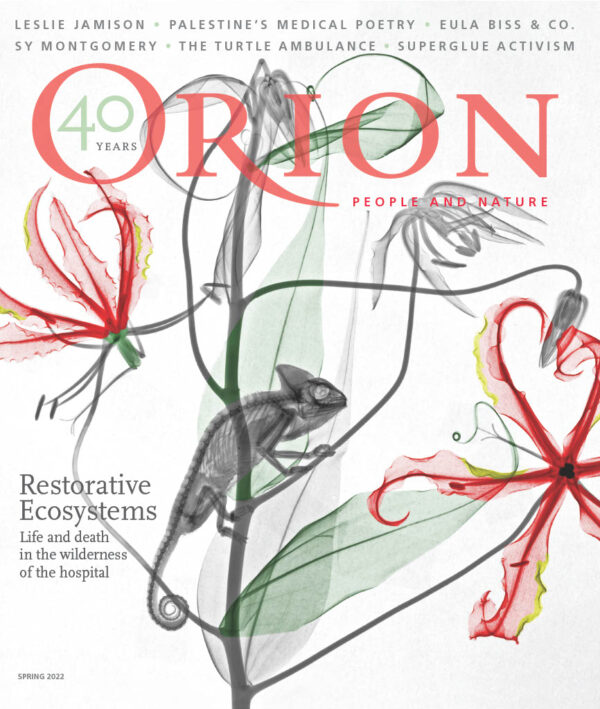

From an aesthetic point of view, the chameleon with hanging begonia (below left).

It is also the one that is most often featured in magazines or shown at exhibitions.

During the x-ray exposure, a wedge was positioned in the x-ray beam, resulting in a gray gradient.

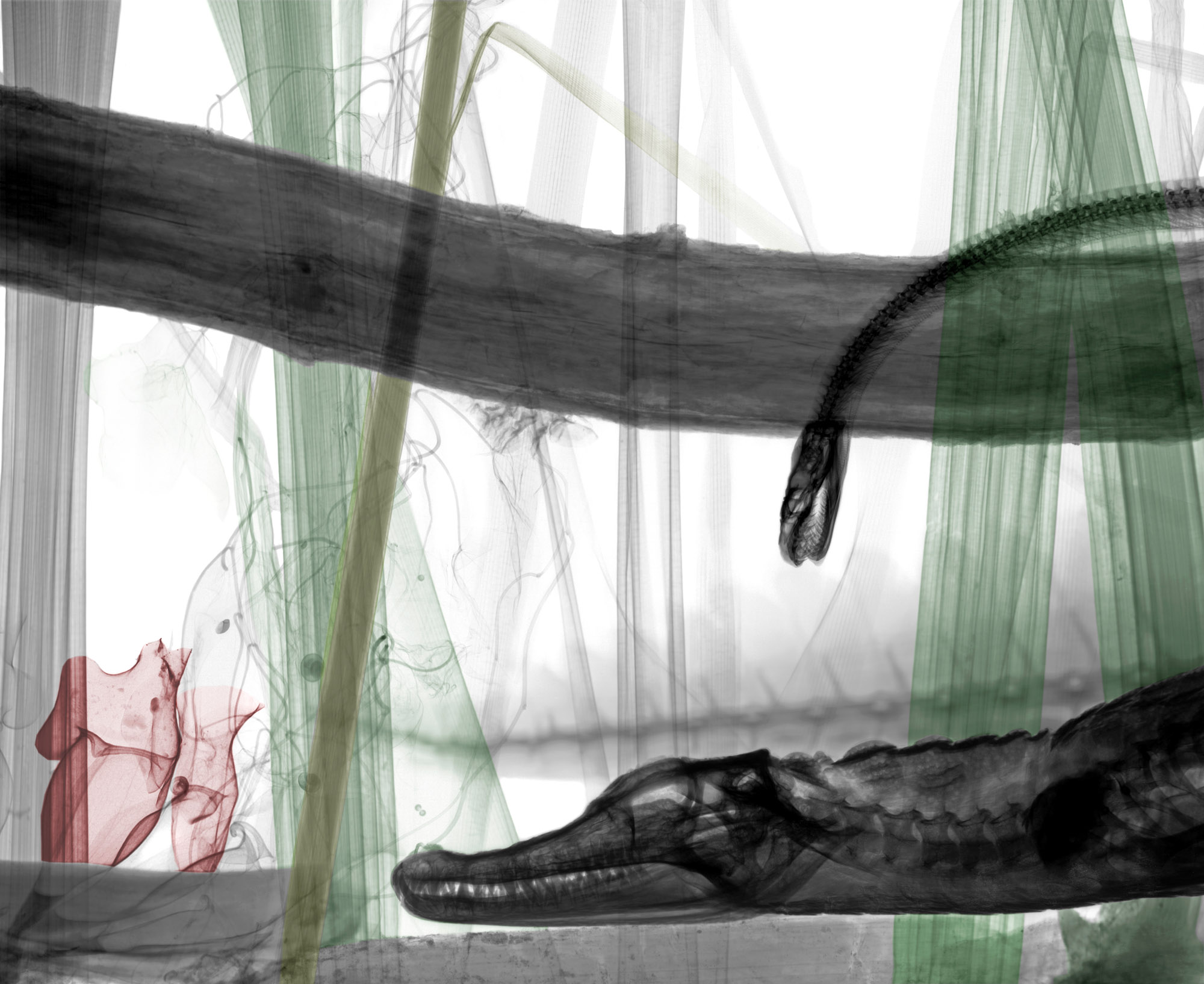

From a technical point of view, the caiman with python (below right).

It was a large biorama. Four x-ray negatives were needed. A horizontal x-ray beam was used, with the x-ray tube on one side and the x-ray negatives on the other side of the biorama.

A difficulty is the enormous difference in x-ray absorption between the thick parts like the skull of the caiman and the very thin parts like the leaves or the plants. To image it all, the biorama was first exposed to low energy x-rays (18 kVp) to depict the thin parts (leaves) immediately followed by an exposure with higher energy (50 kVp) to image the thick parts (caiman). Of course, this last exposure with higher energy decreased the contrast of the thin parts. But that is inevitable, physics. Because of authenticity, the biorama is x-rayed as a whole. The images are not layered on a computer.